Figure A: Tel Aviv University researchers built this self-contained PITA receiver.

Figure A: Tel Aviv University researchers built this self-contained PITA receiver.

Not that long ago, grabbing information from air-gapped computers required sophisticated equipment. In my TechRepublic column Air-gapped computers are no longer secure, researchers at Georgia Institute of Technology explain how simple it is to capture keystrokes from a computer just using spurious electromagnetic side-channel emissions emanating from the computer under attack.

Daniel Genkin, Lev Pachmanov, Itamar Pipman, and Eran Tromer, researchers at Tel Aviv University, agree the process is simple. However, the scientists have upped the ante, figuring out how to ex-filtrate complex encryption data using side-channel technology.

The process

In the paper Stealing Keys from PCs using a Radio: Cheap Electromagnetic Attacks on Windowed Exponentiation (PDF), the researchers explain how they determine decryption keys for mathematically-secure cryptographic schemes by capturing information about secret values inside the computation taking place in the computer.

“We present new side-channel attacks on RSA and ElGamal implementations that use the popular sliding-window or fixed-window (m-ary) modular exponentiation algorithms,” the team writes. “The attacks can extract decryption keys using a low measurement bandwidth (a frequency band of less than 100 kHz around a carrier under 2 MHz) even when attacking multi-GHz CPUs.”

If that doesn’t mean much, this might help: The researchers can extract keys from GnuPG in just a few seconds by measuring side-channel emissions from computers. “The measurement equipment is cheap, compact, and uses readily-available components,” add the researchers. Using that philosophy the university team developed the following attacks.

Software Defined Radio (SDR) attack: This comprises of a shielded loop antenna to capture the side-channel signal, which is then recorded by an SDR program installed on a notebook.

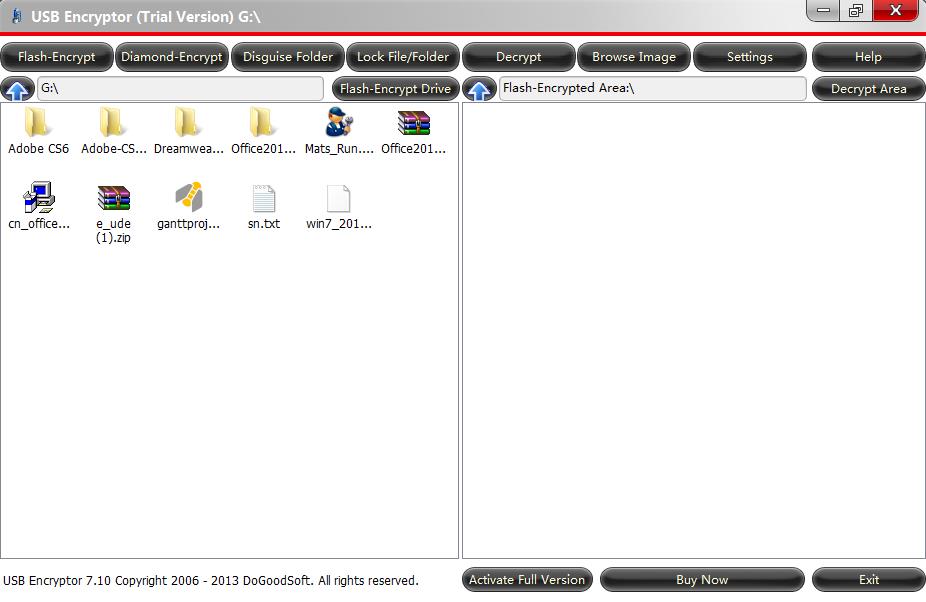

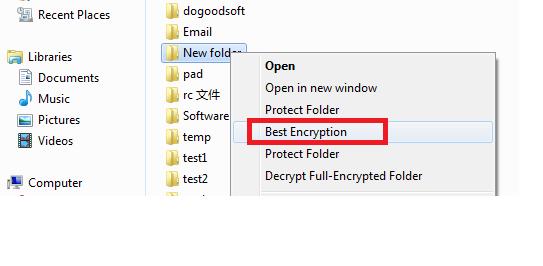

Portable Instrument for Trace Acquisition (PITA) attack: The researchers, using available electronics and food items (who says academics don’t have a sense of humor?), built the self-contained receiver shown in Figure A. The PITA receiver has two modes: online and autonomous.

Online: PITA connects to a nearby observation station via Wi-Fi, providing real-time streaming of the digitized signal.

Autonomous: Similar to online mode, PITA first measures the digitized signal, then records it on an internal microSD card for later retrieval by physical access or via Wi-Fi.

Consumer radio attack: To make an even cheaper version, the team leveraged knowing that side-channel signals modulate at a carrier frequency near 1.7 MHz, which is within the AM radio frequency band. “We used a plain consumer-grade radio receiver to acquire the desired signal, replacing the magnetic probe and SDR receiver,” the authors explain. “We then recorded the signal by connecting it to the microphone input of an HTC EVO 4G smartphone.”

Cryptanalytic approach

This is where the magic occurs. I must confess that paraphrasing what the researchers accomplished would be a disservice; I felt it best to include their cryptanalysis description verbatim:

“Our attack utilizes the fact that, in the sliding-window or fixed window exponentiation routine, the values inside the table of ciphertext powers can be partially predicted. By crafting a suitable ciphertext, the attacker can cause the value at a specific table entry to have a specific structure.

“This structure, coupled with a subtle control flow difference deep inside GnuPG’s basic multiplication routine, will cause a noticeable difference in the leakage whenever a multiplication by this structured value has occurred. This allows the attacker to learn all the locations inside the secret exponent where the specific table entry is selected by the bit pattern in the sliding window. Repeating this process across all table indices reveals the key.”

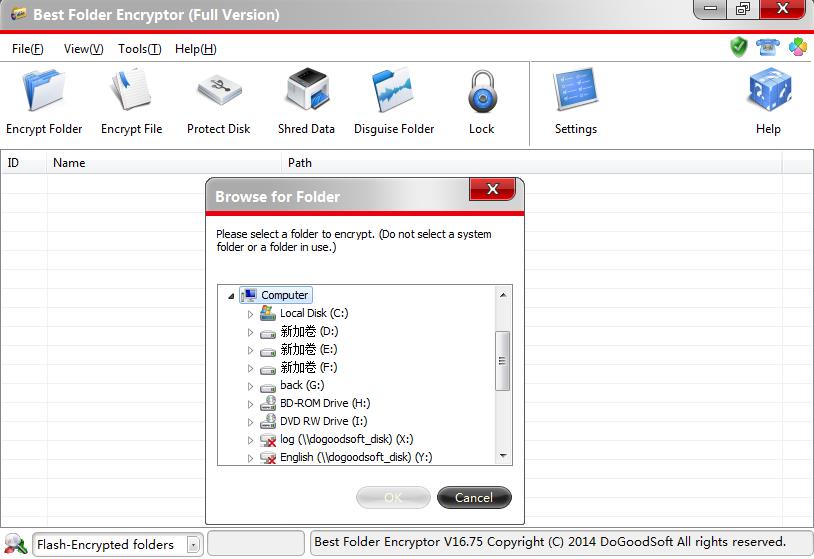

Figure B is a spectrogram displaying measured power as a function of time and frequency for a recording of GnuPG decrypting the same ciphertext using different randomly generated RSA keys. The research team’s explanation:

“It is easy to see where each decryption starts and ends (yellow arrow). Notice the change in the middle of each decryption operation, spanning several frequency bands. This is because, internally, each GnuPG RSA decryption first exponentiates modulo the secret prime p and then modulo the secret prime q, and we can see the difference between these stages.

“Each of these pairs looks different because each decryption uses a different key. So in this example, by observing electromagnetic emanations during decryption operations, using the setup from this figure, we can distinguish between different secret keys.”

Figure B: A spectrogram

Figure B: A spectrogram

Any way to prevent the leakage?

One solution, albeit unwieldy, is operating the computer in a Faraday cage, which prevents any spurious emissions from escaping. “The cryptographic software can be changed, and algorithmic techniques used to render the emanations less useful to the attacker,” mentions the paper. “These techniques ensure the behavior of the algorithm is independent of the inputs it receives.”

Interestingly, the research paper tackles a question about side-channel attacks that TechRepublic readers commented on in my earlier article, “It’s a hardware problem, so why not fix the equipment?”

Basically the researchers mention that the emissions are at such a low level, prevention is impractical because:

Any leakage remnants can often be amplified by suitable manipulation as we do in our chosen-ciphertext attack;

Leakage is often an inevitable side effect of essential performance-enhancing mechanisms.

Something else of interest: the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) considers resistance to side-channel attacks an important evaluation consideration in its SHA-3 competition.

Figure A: Tel Aviv University researchers built this self-contained PITA receiver.

Figure A: Tel Aviv University researchers built this self-contained PITA receiver. Figure B: A spectrogram

Figure B: A spectrogram