Have you heard the one about the Mexican drug kingpin, the eccentric movie star and the Ugly Duckling smartphone that’s all of a sudden the talk of the tech town for all the wrong reasons?

No? Me neither, but recent reports about the role Sean Penn and BlackBerry phones allegedly played in the capture of two-time prison escapee and illegal-substance peddler extraordinaire Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman have all the makings of a classic knee-slapper.

If you just came out of some sort of coma and have no idea about the connection between, Penn, El Chapo, BlackBerry and the hoosegow, you’ll first want to read Penn’s exclusive interview with the wily drug lord on RollingStone.com, in which the leathery actor describes communications between he and Guzman, and Guzman and actress Kate del Castillo, using “a web of BBM devices.” Next, check out this CNN.com story that details the most recent capture of El Chapo, and how it allegedly stemmed from intercepted BlackBerry messages sent between Guzman, his associates and del Castillo last fall.

BlackBerry texts vs. BBM messages vs. BBM Protected

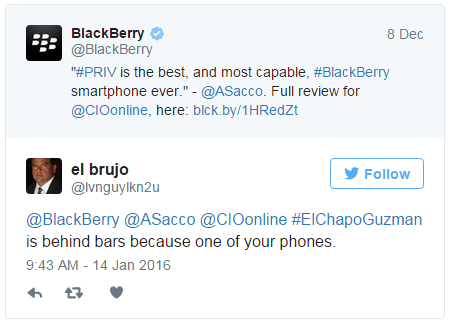

Just yesterday, I received an odd tweet from some random weirdo on Twitter, and it got me thinking about BlackBerry’s role in this whole charade. (See below.)

The majority of stories I found on the subject refer to the messages as “BlackBerry texts,” or something of the like. Based on Penn’s use of the term BBM (he never once writes “BlackBerry” in his many-thousand-word Rolling Stone diatribe, and likely has no idea what BBM stands for) we’ll assume they used BBM and not SMS texts sent via BlackBerry. (Why else would they think BlackBerry messages were more secure than texts?)

Señor Guzman must be a fairly intelligent man, right? I mean, could you escape prison twice and evade Mexican law enforcement for years, while continuing to “supply more heroin, methamphetamine, cocaine and marijuana than anybody else in the world.” (His words, not mine.) However, if he’s so smart, why not use the BBM Protected service, which routes messages through private BlackBerry Enterprise Service (BES) servers so they are truly 100-percent secure and cannot be obtained by law enforcement, according to BlackBerry, as long as recipients are also connected to the same BES. So El Chapo could have simply sent Mr. Spicoli Penn and his other associates secure BlackBerrys and not had to worry. (BBM Protected also encrypts BBM messages sent via the company’s iPhone and Android apps.)

While regular BBM messages are encrypted when they’re sent, BlackBerry uses a “global cryptographic key” that it can use to decrypt BBM messages when they pass through its relay station, according to EncryptedMobile.com. And those decrypted messages can be shared with law enforcement under the right circumstances.

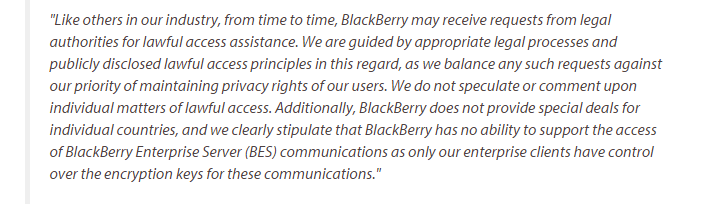

The Mexican government presumably determined that Guzman and his associates were using BBM and served BlackBerry with a lawful access request that just about required the company to hand over those text records. BlackBerry wouldn’t provide a specific comment on the situation, and instead directed me to its Public Policy and Government Relations page, which details its lawful access policies.

From BlackBerry’s lawful access statement:

Note to self: If I ever decide to leave the lucrative world of journalism to take control of a massive criminal syndicate, shell out the extra cash for BES, and make sure to enable BBM Protected.

Smartphone encryption yesterday and today

BlackBerry, a company that’s always been focused on enterprise security, has fought the good fight with various governments over its ability to provide encryption keys for years. BlackBerry went back and forth with the Indian government over encryption demands, for example. And in November, it pulled out of Pakistan after the country demanded access to its customers’ encrypted email and messages, though the government eventually backed down and BlackBerry returned to the market.

BlackBerry’s stance has always been that it cannot and will not provide encryption keys for BES customer data. But governments won’t take no for an answer, and today, other mobile platform providers including Apple and Google must also balance customer privacy needs with government encryption demands.

Just this week, New York State Assemblyman Matt Titone reintroduced a 2015 bill that attempts to require encryption “backdoors” in all smartphones sold in the state, according to TechDirt.com. The bill would reportedly make New York smartphone retailers stop selling devices that don’t have encryption backdoors, which would only hurt New York businesses and lead the state’s residents to simply buy their phones out of state or via black market resellers.

Titone’s bill won’t likely have legs, but it represents the latest (and definitely not the last) attempt by a U.S. lawmaker to circumvent the encryption protections mobile software companies purposefully build into products, which many organizations — legal and illegal — depend on to protect sensitive data.

Of course, unless he pulls off another great escape, it’s too late for encryption to help El Chapo.