French counterterrorism investigators believe that the men suspected in last month’s Paris attacks used widely available encryption tools to communicate with each other, officials familiar with the investigation said, raising questions about whether the men used U.S.-made tools to hide the plot from authorities.

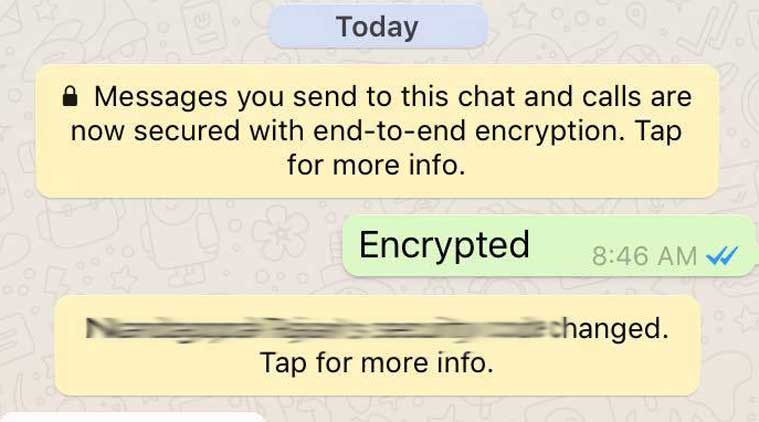

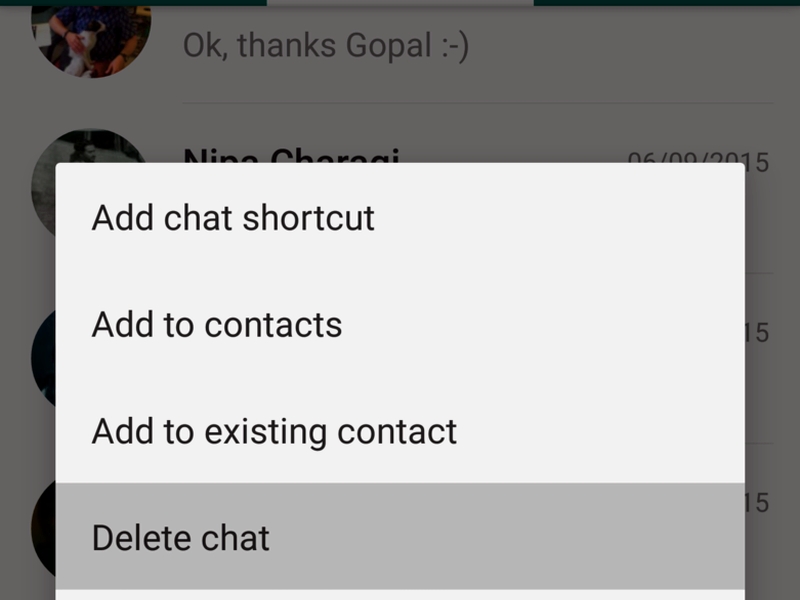

Investigators have previously said that messaging services WhatsApp and Telegram were found on some of the phones of the men suspected in the November attacks that claimed 130 victims. But they had not previously said that the services had been used by the men to communicate with each other in connection with the attacks. The two services are free, encrypted chat apps that can be downloaded onto smartphones. Both use encryption technology that makes it difficult for investigators to monitor conversations.

The findings of the investigation were confirmed by four officials, including one in France, who are familiar with the investigation. All spoke on the condition of anonymity because they were not authorized to speak publicly about the ongoing inquiry. A spokeswoman for the Paris prosecutor’s office, which is leading the investigation, declined to comment.

The investigators’ belief that WhatsApp and Telegram had been used in connection with the attacks was first reported by CNN.

The revelation is likely to add fuel to calls in Congress to force services such as WhatsApp, which is owned by Facebook, to add a back door that would enable investigators to monitor encrypted communications. Such demands have grown stronger in the wake of the Paris attacks and after other attacks in the United States in which the suspects are believed to have communicated securely with Islamic State plotters in Syria.

Already, security hawks in Congress, citing the likelihood that the Paris attackers used encrypted communications, have called for legislation to force companies to create ways to unlock encrypted content for law enforcement. Sen. Dianne Feinstein, D-California, vice-chairman of the Senate Intelligence Committee, has begun working on possible legislation. And Sen. John McCain, R-Arizona, chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee, has promised hearings on the issue, saying, “We’re going to have legislation.”

FBI Director James B. Comey last week cited a May shooting in Garland, Texas, in which two people with assault rifles attempted to attack an exhibit of cartoons of the prophet Muhammad. Investigators believe they were motivated by the Islamic State. Comey told the Senate Judiciary Committee that encrypted technology had prevented investigators from learning the content of communications between the shooters and an alleged foreign plotter.

“That morning, before one of those terrorists left and tried to commit mass murder, he exchanged 109 messages with an overseas terrorist,” Comey told the committee. “We have no idea what he said, because those messages were encrypted.”

Tech firms such as Apple have opposed such calls, saying that such a requirement would render their services and devices less secure and simply send users elsewhere. Apple began placing end-to-end encryption on its chat and video call features several years ago. Then last year, in the wake of revelations by former National Security Agency contractor Edward Snowden about the scope of U.S. surveillance, Apple announced it was offering stronger encryption on its latest iPhones. And more tech firms began to question what had once been routine law enforcement requests to comply with court-ordered wiretaps.

A spokesman for Facebook declined to comment about whether the attackers used WhatsApp. A representative for Germany-based Telegram did not respond to a request for comment.

The officials familiar with the Paris investigation did not say when the services were used, how frequently or for what purpose. One of the officials said investigators believe that the attackers used Telegram’s encrypted chat function more frequently than they used WhatsApp. It was not clear whether authorities were able to obtain “metadata,” information indicating the times and dates of chat messages from either company’s servers. Nor was it clear whether authorities had been able to recover the messages from the phones themselves.

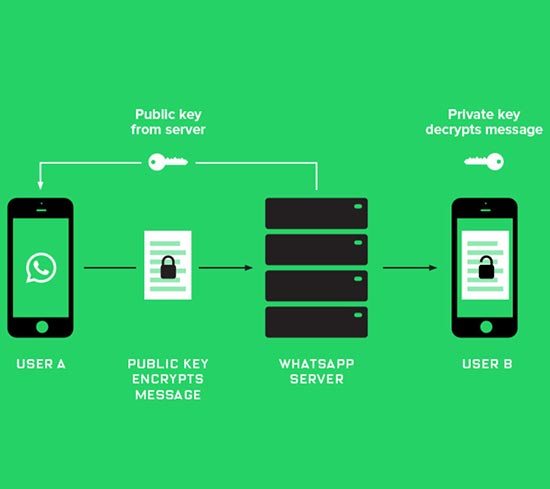

Not all encrypted apps are equal. WhatsApp offers end-to-end encryption between two users on some platforms, such as Android phones. That means the chat content is not visible to Facebook but only to the sender and receiver. WhatsApp is in the process a rollout for Apple’s iPhones. Telegram’s Secret Chat feature is end-to-end encrypted. However, a number of experts say that Telegram is not secure.

“It’s home-brew crypto style,” said Lance James, chief scientist at Flashpoint, a threat intelligence firm. The Telegram developers have “introduced unnecessary risk by making up their own cryptography rules.” He said he was “fairly certain” that advanced spy agencies could find ways around the encryption.

The group chat functions on the apps do not offer end-to-end encryption, which means anyone with access to WhatsApp or Telegram’s servers can read the chats.

European authorities have come under heavy criticism for failing to disrupt the Paris attacks, and it is unclear whether encrypted messaging played an important role in the plot’s success. Ringleader Abdelhamid Abaaoud, a Belgian citizen, was being monitored by European authorities but nevertheless managed to travel to Syria and back this year.

Another suspect, Salah Abdeslam, is still at large despite having been stopped by French police at the Belgian-French border hours after the attacks. He used his real identity documents, but he was not yet in a database, Belgian Interior Minister Jan Jambon told the Belgian VTM broadcaster in an interview aired this week.

“We were simply unlucky,” he said.

Then, investigators believe, Abdeslam went into hiding in a building in the Molenbeek district of Brussels, and Belgian Justice Minister Koen Geens said that a Belgian law banning police raids between 9 p.m. and 5 a.m. may have played a role in his subsequent escape.