For the past six days, citizens have taken to the streets across Iran, protesting government oppression and the rising cost of goods. Video broadcasts from the country have shown increasingly intense clashes between protesters and riot police, with as many as 21 people estimated to have died since the protests began. But a complex fight is also raging online, as protesters look for secure channels where they can organize free of government interference.

![]()

Even before the protest, Iran’s government blocked large portions of the internet, including YouTube, Facebook, and any VPN services that might be used to circumvent the block. The government enforced the block through a combination of centralized censorship by the country’s Supreme Cybercouncil and local ISP interference to enforce more specific orders. The end result is a sometimes haphazard system that can still have devastating effects on any service the regime sees as a threat.

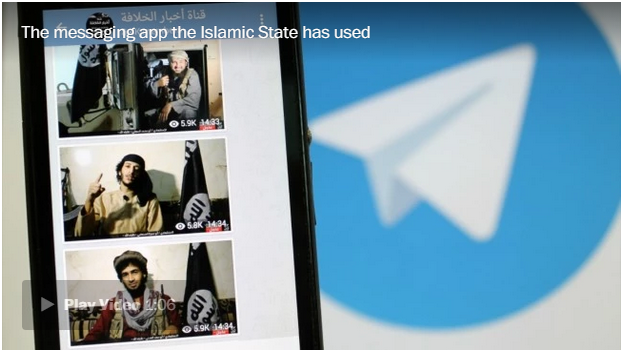

For years, Iran’s most popular encrypted messenger has been Telegram. While some cryptographers have criticized Telegram’s homebrew cryptography, local Iranian users have cared more about the app’s independence from the United States. (The app’s core development team is based in Russia, making it less vulnerable to US government requests.) The app’s massive group chats proved popular, and the government was content to target individual users, occasionally hacking accounts by intercepting account reset messages sent to the user’s phone number.

As protests intensified, Telegram has become both a tool for organizers and a target for the regime. On Saturday, Telegram suspended the popular Amad News channel for violating the service’s policy against calls to violence. One conversation was publicly called out by Iran’s Minister of Technology for recommending protesters attack police with Molotov cocktails. According to Telegram founder Pavel Durov, the government also requested suspensions for a number of other channels that had not violated the policy on violence. When Telegram refused, the government placed a nationwide block on the app.

The government also banned Instagram, although government representatives insist both bans are temporary and will be lifted once protests subside.

The most popular alternative among US activists is Signal, which offers similar group chat features with more robust encryption — but Signal is blocked in Iran for an entirely different reason. The app relies on the Google AppEngine to disguise its traffic through a process called “domain fronting.” The result makes it hard to detect Signal traffic amid the mess of Google requests — but it also means that wherever Google is unavailable, Signal is unavailable too.

At the same time, Google appears to have blocked Iranian access to AppEngine to comply with US sanctions. After years of diplomatic pressure, US companies face significant regulations on any technology exported to Iran, and it’s often unclear how those rules extend to cloud services like AppEngine. Still, researchers like Collin Anderson say Google could find a way to whitelist Signal in Iran if the company wanted to. (Google declined to comment when reached by The Verge.)

Still, the blocks leave organizers in a difficult place, with no clear way to coordinate activity across groups that often sprawl to hundreds of thousands of people. WhatsApp is still available in the country, although bans on the service have been proposed in the past.