President Obama recently called on the best minds in government, the tech sector and academia to help develop a policy consensus around “strong encryption” — powerful technologies that can thwart hackers and provide a profound new level of cybersecurity, but also put data beyond the reach of court-approved subpoenas.

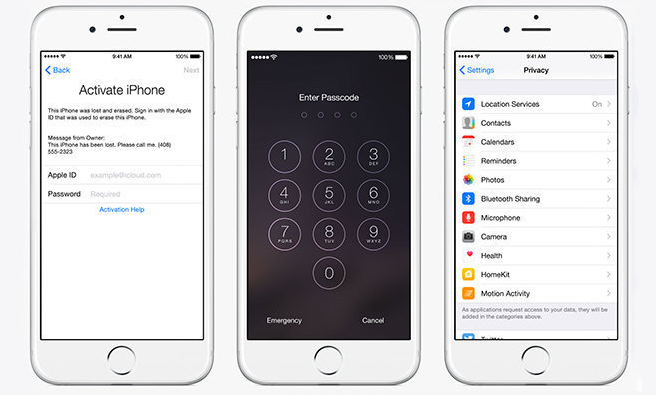

From Obama on down, government officials stressed that they are not asking the technology sector to build “back doors” that would allow law enforcement and intelligence agencies to obtain communications in the event of criminal or terrorist acts.

That prospect drew an extremely negative reaction from the techies — and is still chilling the government-industry dialogue over the issue.

Instead, the government is saying that tech and communications companies themselves should have some way to unlock encrypted messages if law enforcement shows up with a subpoena.

Access to such messages could, in theory, be vital in real-time crises. Skeptical lawmakers have said federal officials have offered no empirical data suggesting this has been a problem.

“One of the big issues … that we’re focused on, is this encryption issue,” Obama said during a Sept. 16 appearance before the Business Roundtable. “And there is a legitimate tension around this issue.”

Obama explained: “On the one hand, the stronger the encryption, the better we can potentially protect our data. And so there’s an argument that says we want to turbocharge our encryption so that nobody can crack it.”

But it wasn’t as simple as that.

“On the other hand,” Obama said, “if you have encryption that doesn’t have any way to get in there, we are now empowering ISIL, child pornographers, others to essentially be able to operate within a black box in ways that we’ve never experienced before during the telecommunications age. And I’m not talking, by the way, about some of the controversies around [National Security Agency surveillance]; I’m talking about the traditional FBI going to a judge, getting a warrant, showing probable cause, but still can’t get in.”

According to the president, law enforcement, the tech community and others are engaged in “a process … to see if we can square the circle here and reconcile the need for greater and greater encryption and the legitimate needs of national security and law enforcement.”

Obama summed up: “And I won’t say that we’ve cracked the code yet, but we’ve got some of the smartest folks not just in government but also in the private sector working together to try to resolve it. And what’s interesting is even in the private sector, even in the tech community, people are on different sides of this thing.”

However, the tech sector, writ large, has shown little interest in negotiating over strong encryption.

After a recent hearing of the House Intelligence Committee, Rep. Adam Schiff, D-Calif., said technology companies want the government to spell out what it wants, and that techies simply will not craft a policy in an area that should be free from government interference.

Tech companies are deeply concerned that American-made products will be seen in the global marketplace as tainted if they reach some kind of accommodation with the government. It’s all part of the continued international blowback from the revelations by ex-NSA contractor Edward Snowden, tech groups say.

Schiff visited with several Silicon Valley-based companies over the recent summer recess. “I was impressed by the companies’ position — it’s hard to refute. But what was unusual, more than one of the companies said government should provide its [proposed] answer in order to advance the discussion,” he said.

The tech sector, Schiff said, is unlikely to advance a policy position other than its opposition to any mandated “back door.”

“But there has to be some kind of resolution, even if it is acceptance of the status quo.”

Schiff and other lawmakers, including Senate Judiciary Chairman Charles Grassley, R-Iowa, are trying to encourage a dialogue between the tech sector and law enforcement.

FBI Director James Comey testified before the House Intelligence panel that such talks are underway, and have been productive so far.

“First of all, I very much appreciate the feedback from the companies,” Comey said at the Sept. 10 Intelligence Committee hearing. “We’ve been trying to engage in dialogue with companies, because this is not a problem that’s going to be solved by the government alone; it’s going to require industry, academia, associations of all kinds and the government.”

He stressed: “I hope we can start from a place we all agree there’s a problem and that we share the same values around that problem. … We all care about safety and security on the Internet, right? I’m a big fan of strong encryption. We all care about public safety.”

It was an extremely complicated policy problem, Comey agreed, but added, “I don’t think we’ve really tried. I also don’t think there’s an ‘it’ to the solution. I would imagine there might be many, many solutions depending upon whether you’re an enormous company in this business, or a tiny company in that business. I just think we haven’t given it the shot it deserves, which is why I welcome the dialogue. And we’re having some very healthy discussions.”

Tech sources contacted after the hearing suggested that Comey was overstating the level of dialogue now taking place.

The Obama administration has signaled that it isn’t looking for a legislative solution, which is just as well, because lawmakers including Schiff and Grassley have said that is a highly unlikely prospect.

But the administration probably needs to give a clearer signal of what it would like to see at the end of this dialogue before the tech side agrees to fully engage.