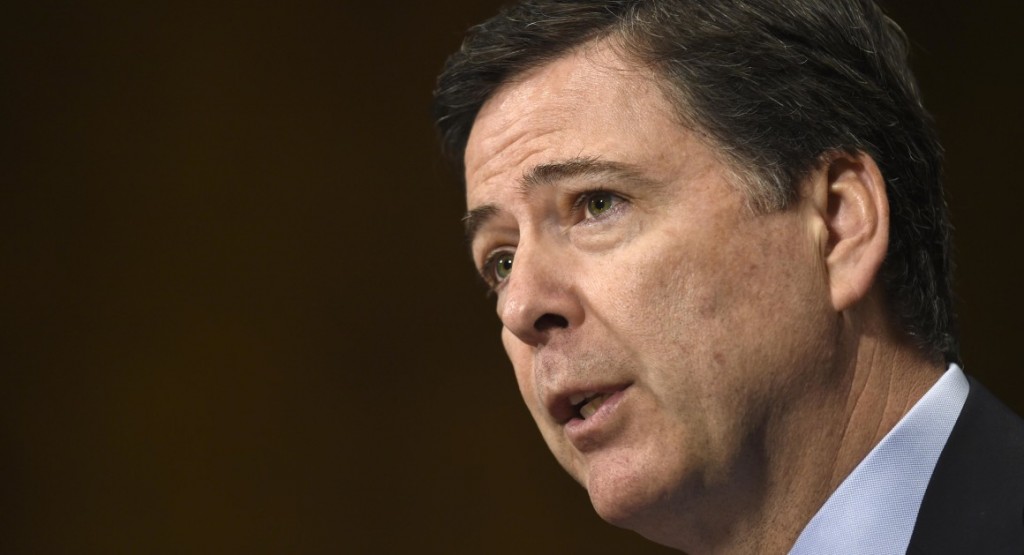

By July 2015, FBI Director Jim Comey knew he was losing the battle against sophisticated technologies that allowed criminals to communicate without fear of government surveillance.

In back-to-back congressional hearings that month, Comey struggled to make the case that terrorists and crooks were routinely using such encryption systems to evade the authorities. He conceded that he had no real answer to the problem and agreed that all suggested remedies had major drawbacks. Pressed for specifics, he couldn’t even say how often bureau investigations had been stymied by what he called the “going dark” problem.

“We’re going to try and do that for you, but I’m not optimistic we’re going to be able to get you a great data set,” he told lawmakers.

This week, Comey was back before Congress with a retooled sales pitch. Gone were the vague allusions to ill-defined problems. In their place: a powerful tale of the FBI’s need to learn what is on an encrypted iPhone used by one of the terrorists who killed 14 people in California. “Maybe the phone holds the clue to finding more terrorists. Maybe it doesn’t,” Comey wrote shortly before testifying. “But we can’t look the survivors in the eye, or ourselves in the mirror, if we don’t follow this lead.”

The tactical shift has won Comey tangible gains. After more than a year of congressional inaction, two prominent lawmakers, Sen. Mark Warner (D-Va.) and House Homeland Security Chairman Michael McCaul (R-Texas), have proposed a federal commission that could lead to encryption legislation. Several key lawmakers, who previously hadn’t chosen sides over encryption, such as Rep. Jim Langevin (D-RI), are siding with the administration in its legal battle with Apple. Likewise, several former national security officials — such as former National Security Agency chief Gen. Michael Hayden and former Director of National Intelligence Mike McConnell — who lined up with privacy advocates in the past have returned to the government side in this case.

“The public debate was not going the FBI’s way and it appears there’s been a deliberate shift in strategy,” said Mike German, a former FBI special agent. “They realized…that the most politically tenable argument was going to be ‘we need access when we have a warrant and in a serious criminal case. All the better if it’s a terrorism case.’”

The catalyst for change has been a high-stakes legal fight in a central California courtroom where Apple seeks to overturn a judge’s order to write new software to help the FBI circumvent an iPhone passcode. Other technology companies such as Microsoft, Google, Facebook and Twitter this week rallied to Apple’s side. The Justice Department, meanwhile, has drawn supporting legal briefs from law enforcement associations as well as families of the San Bernardino victims.

Comey’s evolution may have been foreshadowed last summer. In an August email, Robert Litt, the intelligence community’s top lawyer, wrote colleagues that the mood on Capitol Hill “could turn in the event of a terrorist attack or criminal event where strong encryption can be shown to have hindered law enforcement,” according to The Washington Post.

The Dec. 2 San Bernardino attack, coming less than three weeks after a coordinated series of Islamic State shootings and bombing killed at least 130 people in Paris, reignited law enforcement concern about terrorists’ ability to shield their plotting via encryption. The San Bernardino killers, Syed Farook and his wife Tashfeen Malik, destroyed two cellphones before dying in a gun battle with police. Investigators discovered the iPhone at issue in the courtroom fight inside the Farook family’s black Lexus sedan.

To be sure, Comey’s new strategy thus far has paid only limited dividends. The Warner-McCaul commission, if it is ever formed, may or may not change U.S. encryption policy. Renewed support from former officials, such as Hayden and McConnell, extends only to the San Bernardino case.

Indeed, the FBI director’s hopes for an enduring solution to “the going dark” problem remain aspirational. The White House last fall abandoned plans to seek legislation mandating a technological fix for authorities’ encryption headaches. And since then, the Obama administration has confined itself to jawboning Silicon Valley.

But in choosing to make a fight over the iPhone used by one of the San Bernardino terrorists, Comey has selected an advantageous battlefield. Many encryption supporters say that the San Bernardino case isn’t really about encryption because the FBI is asking Apple to build custom software that bypasses the phone’s passcode, a separate though related security feature. That distinction, however, may be lost on the public and many members of Congress. Some have even speculated the FBI is using the San Bernardino massacre to revive an encryption debate that it appeared to have lost.

“It appears to me they’re using this case specifically to try to enact a policy proposal they could not get through Congress last year,” said Rep. Ted Lieu (D-Calif.), an encryption advocate. “It’s clear to me that the FBI is trying to use this case to influence the public.”

The fight with Apple not only carries the emotional heft of terrorism, but — thanks to the distinction between encryption backdoors and passcode subversion — has drawn many of Comey’s most vocal critics from the national security community back into the fold.

Hayden, the former NSA head, and McConnell, the nation’s ex-intelligence czar, opposed Congress mandating the creation of technological “back doors” for the government to exploit. Yet, on the Apple case, they side with Comey.

“The FBI made this a test case and that was very deliberate on their part, to refocus the conversation,” said Robert Cattanach, a former Justice Department prosecutor. “This is not some abstract principle of privacy versus government overreach. There are real impacts.”

The San Bernardino case could be a win-win for Comey. If Apple prevails in court, Congress might respond by intervening with legislation. Both the FBI and Apple have said Congress is better equipped to manage the issue than courts.

The legal battles also may discourage companies from building strong encryption given the risk of future legal showdowns, said German, who is now a fellow with the Brennan Center for Justice.

“This is less about Apple than about the developer who is sitting in his garage right now creating the next big thing,” he said. “The idea is to make that person realize that the stronger they build the security the harder it will be for them when they get that order to unlock it to do so. There’s an incentive to build a crack in the system.”