Oracle execs used the final keynote of this week’s OpenWorld to praise their Sparc M7 processor’s ability to accelerate encryption and some SQL queries in hardware.

On Wednesday, John Fowler, veep of systems at Oracle, said the M7 microprocessor and its builtin coprocessors that speed up crypto algorithms and database requests stood apart from the generic Intel x86 servers swelling today’s data center racks.

“I don’t believe that the million-server data center powered by a hydroelectric dam is the scalable future of enterprise computing,” Fowler said. “We’ll need to keep doing it, but we also need to invest in new technology so you all don’t have to build them.”

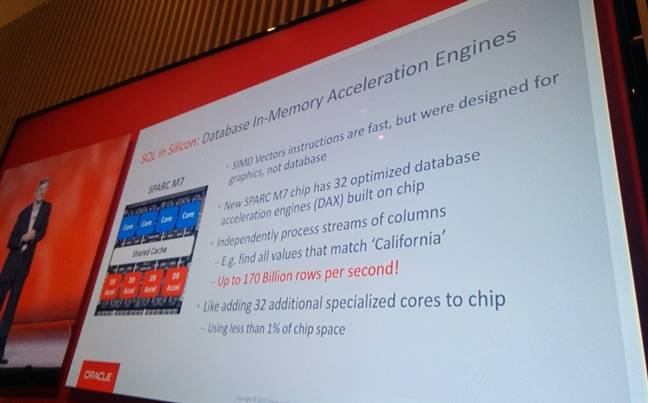

He told the crowd that Oracle has spent the past five years working out how to build a chip that can handle some SQL database queries in hardware, offloading the job from the main processor cores.

The new Sparc has eight in-memory database acceleration engines that are capable of blitzing through up to 170 billion rows per second, apparently. The acceleration is limited by the memory subsystem, which tops out at 160GB/s. Each of the eight engines has four pipelines, which adds up to 32 processing units.

According to Oracle, an acceleration engine can read in chunks of compressed columnar databases, evaluate a query on those columns while decompressing the information, and then spit out the result. While powerful, these engines are tiny and account for less than one per cent of the M7 chip’s acreage, Fowler said.

Essentially, the hardware is tuned for performing analytics at high-speed on in-memory columnar databases. Decompression is more important than compression for handling information fast, Fowler said, and the decision to build in specific hardware to handle it all makes the M7 very speedy. Very speedy at running Oracle Database, anyway.

To access these engines, you need to use an Oracle software library that abstracts away the specifics of the hardware: the library queues up SQL queries for the coprocessors to process, much like firing graphics commands into a GPU. Naturally, Oracle Database takes advantage of this library.

Oracle has taken the same hardware approach to encryption, too. Inside the M7 are accelerators capable of running 15 crypto algorithms, including AES and Diffie-Hellman, although at least two of these – DES and SHA-1 – are considered to be broken by now. Hardware accelerated crypto is standard issue now in today’s microprocessors, from Intel and AMD CPUs to ARM-compatible system-on-chips.

As a result of these accelerators, the M7 chip is 4.5 times as fast as IBM’s Power8 processors, Fowler claimed, and in Oracle systems the processor handled encrypted data only 2.8 per cent more slowly than the same data unencrypted. The cryptographic capabilities of the chip don’t just work for Oracle code, Fowler said, but also in third-party Solaris applications.

“We’ve picked up the pace of silicon development,” he concluded. “This is our sixth processor in five years, with many more to come.”

Timothy Prickett Morgan, co-editor of our sister site The Platform said the M7 has 10 billion 20nm transistor gates, and its database analytics engines are available to any programs running on Solaris.

“The Sparc M7 processors made their debut at the Hot Chips conference in 2014, and it is one of the biggest, baddest server chips on the market,” Prickett Morgan added in his in-depth analysis on Wednesday.

“And with the two generations of ‘Bixby’ interconnects that Oracle has cooked up to create ever-larger shared memory systems, Oracle could put some very big iron with a very large footprint into the field, although it has yet to push those interconnects to their limits.”