When the NSA subcontractor Edward Snowden released classified documents in June 2013 baring the U.S. intelligence community’s global surveillance programs, it revealed the lax attention to privacy and data security at major Internet companies like Apple, Google, Yahoo, and Microsoft. Warrantless surveillance was possible because data was unencrypted as it flowed between internal company data centers and service providers.

The revelations damaged technology companies’ relationships with businesses and consumers. Various estimates pegged the impact at between $35 billion and $180 billion as foreign business customers canceled service contracts with U.S. cloud computing companies in favor of foreign competitors, and as the companies poured money into PR campaigns to reassure their remaining customers.

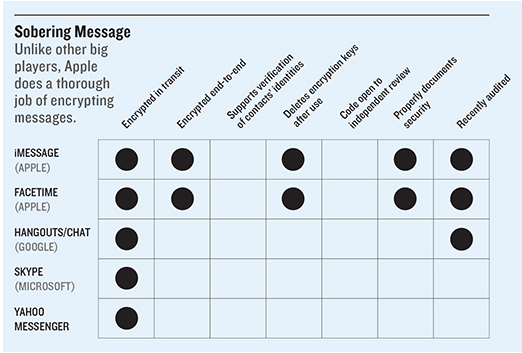

There was a silver lining: the revelations catalyzed a movement among technology companies to use encryption to protect users’ data from spying and theft. But the results have been mixed. Major service providers including Google, Yahoo, and Microsoft—who are among the largest providers of cloud- and Web-based services like e-mail, search, storage, and messaging—have indeed encrypted user data flowing across their internal infrastructure. But the same isn’t true in other contexts, such as when data is stored on smartphones or moving across networks in hugely popular messaging apps like Skype and Google Hangouts. Apple is leading the pack: it encrypts data by default on iPhones and other devices running newer versions of its operating system, and it encrypts communications data so that only the sender and receiver have access to it.

When the NSA subcontractor Edward Snowden released classified documents in June 2013 baring the U.S. intelligence community’s global surveillance programs, it revealed the lax attention to privacy and data security at major Internet companies like Apple, Google, Yahoo, and Microsoft. Warrantless surveillance was possible because data was unencrypted as it flowed between internal company data centers and service providers.

The revelations damaged technology companies’ relationships with businesses and consumers. Various estimates pegged the impact at between $35 billion and $180 billion as foreign business customers canceled service contracts with U.S. cloud computing companies in favor of foreign competitors, and as the companies poured money into PR campaigns to reassure their remaining customers.

There was a silver lining: the revelations catalyzed a movement among technology companies to use encryption to protect users’ data from spying and theft. But the results have been mixed. Major service providers including Google, Yahoo, and Microsoft—who are among the largest providers of cloud- and Web-based services like e-mail, search, storage, and messaging—have indeed encrypted user data flowing across their internal infrastructure. But the same isn’t true in other contexts, such as when data is stored on smartphones or moving across networks in hugely popular messaging apps like Skype and Google Hangouts. Apple is leading the pack: it encrypts data by default on iPhones and other devices running newer versions of its operating system, and it encrypts communications data so that only the sender and receiver have access to it.

But Apple products aren’t widely used in the poor world. Of the 3.4 billion smartphones in use worldwide, more than 80 percent run Google’s Android operating system. Many are low-end phones with less built-in protection than iPhones. This has produced a “digital security divide,” says Chris Soghoian, principal technologist at the American Civil Liberties Union. “The phone used by the rich is encrypted by default and cannot be surveilled, and the phone used by most people in the global south and the poor and disadvantaged in America can be surveilled,” he said at MIT Technology Review’s EmTech conference in November.

Pronouncements on new encryption plans quickly followed the Snowden revelations. In November 2013, Yahoo announced that it intended to encrypt data flowing between its data centers and said it would also encrypt traffic moving between a user’s device and its servers (as signaled by the address prefix HTTPS). Microsoft announced in November and December 2013 that it would expand encryption to many of its major products and services, meaning data would be encrypted in transit and on Microsoft’s servers. Google announced in March 2014 that connections to Gmail would use HTTPS and that it would encrypt e-mails sent to other providers who can also support encryption, such as Yahoo. And finally, in 2013 and 2014, Apple implemented the most dramatic changes of all, announcing that the latest version of iOS, the operating system that runs on all iPhones and iPads, would include built-in end-to-end encrypted text and video messaging. Importantly, Apple also announced it would store the keys to decrypt this information only on users’ phones, not on Apple’s servers—making it far more difficult for a hacker, an insider at Apple, or even government officials with a court order to gain access.

Google, Microsoft, and Yahoo don’t provide such end-to-end encryption of communications data. But users can turn to a rising crop of free third-party apps, like ChatSecure and Signal, that support such encryption and open their source code for review. Relatively few users take the extra step to learn about and use these tools. Still, secure messaging apps may play a key role in making it easier to implement wider encryption across the Internet, says Stephen Farrell, a computer scientist at Trinity College Dublin and a leader of security efforts at the Internet Engineering Task Force, which develops fundamental Internet protocols. “Large messaging providers need to get experience with deployment of end-to-end secure messaging and then return to the standards process with that experience,” he says. “That is what will be needed to really address the Internet-scale messaging security problem.”