The NSA could have gained a significant amount of its access to the world’s encrypted communications thanks to the high-tech version of reusing passwords, according to a report from two US academics.

Computer scientists J Alex Halderman and Nadia Heninger argue that a common mistake made with a regularly used encryption protocol leaves much encrypted traffic open to eavesdropping from a well-resourced and determined attacker such as the US national security agency.

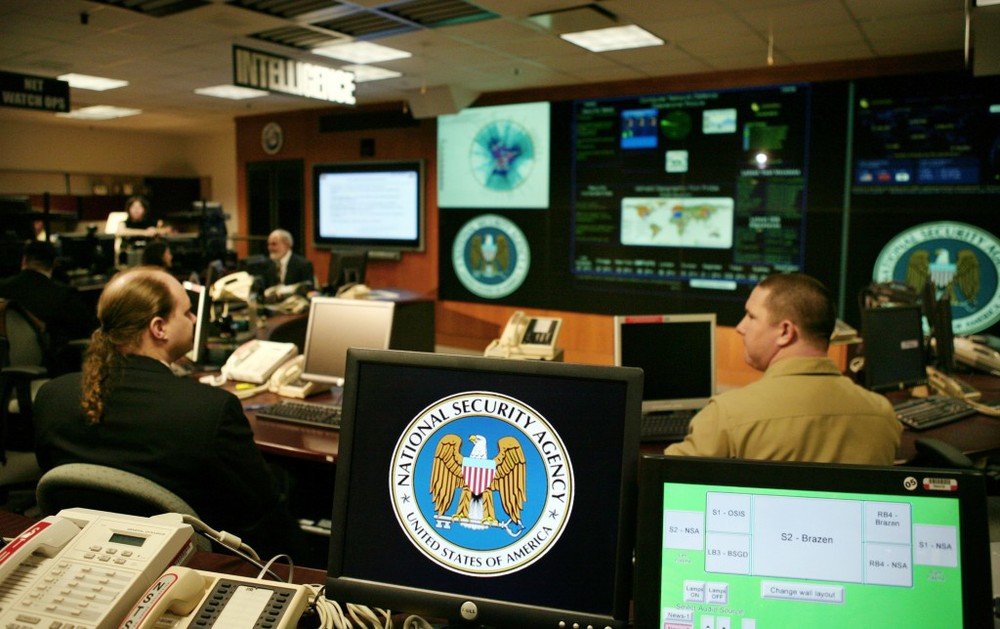

The information about the NSA leaked by Edward Snowden in the summer of 2013 revealed that the NSA broke one sort of encrypted communication, virtual private networks (VPN), by intercepting connections and passing some data to the agency’s supercomputers, which would then return the key shortly after. Until now, it was not known what those supercomputers might be doing, or how they could be returning a valid key so quickly, when attacking VPN head-on should take centuries, even with the fastest computers.

The researchers say the flaw exists in the way much encryption software applies an algorithm called Diffie-Hellman key exchange, which lets two parties efficiently communicate through encrypted channels.

A form of public key cryptography, Diffie-Hellman lets users communicate by swapping “keys” and running them through an algorithm which results in a secret key that both users know, but no-one else can guess. All the future communications between the pair are then encrypted using that secret key, and would take hundreds or thousands of years to decrypt directly.

But the researchers say an attacker may not need to target it directly. Instead, the flaw lies in the exchange at the start of the process. Each person generates a public key – which they tell to their interlocutor – and a private key, which they keep secret. But they also generate a common public key, a (very) large prime number which is agreed upon at the start of the process.

Since those prime numbers are public anyway, and since it is computationally expensive to generate new ones, many encryption systems reuse them to save effort. In fact, the researchers note, one single prime is used to encrypt two-thirds of all VPNs and a quarter of SSH servers globally, two major security protocols used by a number of businesses. A second is used to encrypt “nearly 20% of the top million HTTPS websites”.

The problem is that, while there’s no need to keep the chosen prime number secret, once a given proportion of conversations are using it as the basis of their encryption, it becomes an appealing target. And it turns out that, with enough money and time, those commonly used primes can become a weak point through which encrypted communications can be attacked.

In their paper, the two researchers, along with a further 12 co-authors, describe their process: a single, extremely computationally intensive “pre-calculation” which “cracks” the chosen prime, letting them break communications encrypted using it in a matter of minutes.

How intensive? For “shorter” primes (512 bits long, about 150 decimal digits), the precalcuation takes around a week – crippling enough that, after it was disclosed with the catchy name of “Logjam”, major browsers were changed to reject shorter primes in their entirety. But even for the gold standard of the protocol, using a 1024-bit prime, a precalculation is possible, for a price.

The researchers write that “it would cost a few hundred million dollars to build a machine, based on special purpose hardware, that would be able to crack one Diffie-Hellman prime every year.”

“Based on the evidence we have, we can’t prove for certain that NSA is doing this. However, our proposed Diffie-Hellman break fits the known technical details about their large-scale decryption capabilities better than any competing explanation.”

There are ways around the problem. Simply using a unique common prime for each connection, or even for each application, would likely reduce the reward for the year-long computation time so that it was uneconomical to do so. Similarly, switching to a newer cryptography standard (“elliptic curve cryptography”, which uses the properties of a particular type of algebraic curve instead of large prime numbers to encrypt connections) would render the attack ineffective.

But that’s unlikely to happen fast. Some occurrences of Diffie-Hellman literally hard-code the prime in, making it difficult to change overnight. As a result, “it will be many years before the problems go away, even given existing security recommendations and our new findings”.

“In the meantime, other large governments potentially can implement similar attacks, if they haven’t already.”