After months of deliberation, the Obama administration has made a long-awaited decision on the thorny issue of how to deal with encrypted communications: It will not — for now — call for legislation requiring companies to decode messages for law enforcement.

Rather, the administration will continue trying to persuade companies that have moved to encrypt their customers’ data to create a way for the government to still peer into people’s data when needed for criminal or terrorism investigations.

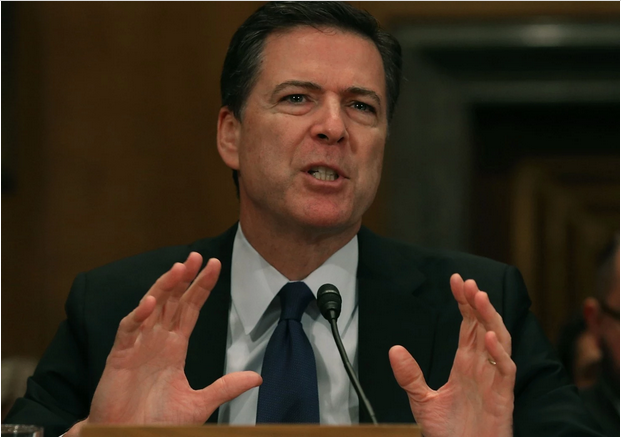

“The administration has decided not to seek a legislative remedy now, but it makes sense to continue the conversations with industry,” FBI Director James Comey said at a Senate hearing Thursday of the Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee.

The decision, which essentially maintains the status quo, underscores the bind the administration is in — between resolving competing pressures to help law enforcement and protecting consumer privacy.

The FBI says it is facing an increasing challenge posed by the encryption of communications of criminals, terrorists and spies. A growing number of companies have begun to offer encryption in which the only people who can read a message, for instance, are the person who sent it and the person who received it. Or, in the case of a device, only the device owner has access to the data. In such cases, the companies themselves lack “backdoors” or keys to decrypt the data for government investigators, even when served with search warrants or intercept orders.

The decision was made at a Cabinet meeting Oct. 1.

“As the president has said, the United States will work to ensure that malicious actors can be held to account – without weakening our commitment to strong encryption,” National Security Council spokesman Mark Stroh said. “As part of those efforts, we are actively engaged with private companies to ensure they understand the public safety and national security risks that result from malicious actors’ use of their encrypted products and services.”

But privacy advocates are concerned that the administration’s definition of strong encryption also could include a system in which a company holds a decryption key or can retrieve unencrypted communications from its servers for law enforcement.

“The government should not erode the security of our devices or applications, pressure companies to keep and allow government access to our data, mandate implementation of vulnerabilities or backdoors into products, or have disproportionate access to the keys to private data,” said Savecrypto.org, a coalition of industry and privacy groups that has launched a campaign to petition the Obama administration.

To Amie Stepanovich, the U.S. policy manager for Access, one of the groups signing the petition, the status quo isn’t good enough. “It’s really crucial that even if the government is not pursuing legislation, it’s also not pursuing policies that will weaken security through other methods,” she said.

The FBI and Justice Department have been talking with tech companies for months. On Thursday, Comey said the conversations have been “increasingly productive.” He added: “People have stripped out a lot of the venom.”

He said the tech executives “are all people who care about the safety of America and also care about privacy and civil liberties.”

Comey said the issue afflicts not just federal law enforcement but also state and local agencies investigating child kidnappings and car crashes— “cops and sheriffs … [who are] increasingly encountering devices they can’t open with a search warrant.”

One senior administration official said the administration thinks it’s making enough progress with companies that seeking legislation now is unnecessary. “We feel optimistic,” said the official, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to describe internal discussions. “We don’t think it’s a lost cause at this point.”

Legislation, said Rep. Adam Schiff (D-Calif.), is not a realistic option given the current political climate. He said he made a recent trip to Silicon Valley to talk to Twitter, Facebook and Google. “They quite uniformly are opposed to any mandate or pressure — and more than that, they don’t want to be asked to come up with a solution,” Schiff said.

Law enforcement officials know that legislation is a tough sell now. But, one senior official stressed, “it’s still going to be in the mix.”

On the other side of the debate, technology, diplomatic and commerce agencies were pressing for an outright statement by Obama to disavow a legislative mandate on companies. But their position did not prevail.

Daniel Castro, vice president of the Information Technology & Innovation Foundation, said absent any new laws, either in the United States or abroad, “companies are in the driver’s seat.” He said that if another country tried to require companies to retain an ability to decrypt communications, “I suspect many tech companies would try to pull out.”