The Justice Department and Microsoft go head-to-head in the U.S. Second Circuit Court of Appeals in Manhattan on Wednesday. The battleground? Data privacy.

At issue is the question of whether U.S. law enforcement can use a search warrant — in this case, in a drug investigation — to force the U.S.-based technology company to turn over emails it has stored in a data center in Ireland. Lower courts have sided with the government and held Microsoft in contempt for refusing to comply with the search warrant. Microsoft has appealed, arguing that its data center is subject to Irish and European privacy laws and outside the jurisdiction of U.S. authorities.

Civil liberties and internet-privacy advocates are watching the case closely, as are company and law-enforcement lawyers. They’re also watching another case, also involving a drug investigation, in which Apple was served with a court order instructing it to turn over text messages between iPhone owners.

After the Edward Snowden revelations, U.S. technology and telecom companies were criticized for allegedly letting the government spy on Americans’ emails, texts and video chats.

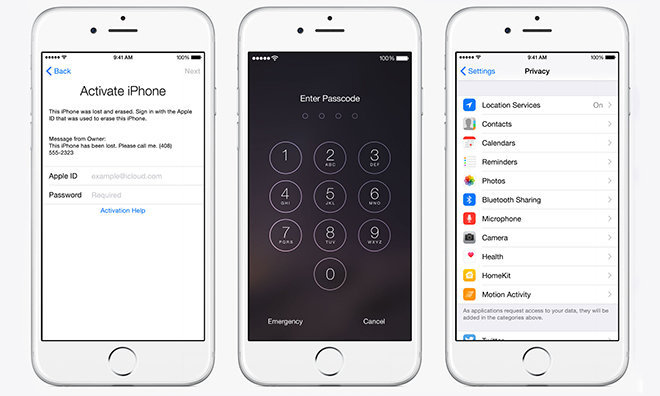

Many companies have been fighting back, hoping to burnish their images as protector of their client data privacy. Microsoft is fighting government access to overseas data centers. Apple has been rolling out strong “end-to-end” encryption, in which only the software in the sender’s and receiver’s devices (an iPhone or iPad) have the the requisite keys to decode the message. That means there’s no “back-door key” that could unlock an email or other communication. In addition, both Apple and Google have deployed private-code locking systems that make their smartphones essentially unbreakable, except by the phone’s owner, who sets the code.

“This way, the companies don’t open up the device,” says Peter Swire, an expert on computer security at Georgia Tech who served on President Obama’s task force on surveillance and cybersecurity. “The companies don’t have access to the content between Alice and Bob.”

If the company that made the device, or is carrying the communication on its network, can’t eavesdrop on users like Alice and Bob, he says, the FBI and other outside parties can’t either.

FBI director James Comey has said these new strong encryption technologies are making communications “go dark” for law enforcement. He claims the companies deploying this kind of encryption are hampering law-enforcement investigations.

But Nate Cardozo, a staff attorney at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, says law enforcement will just have to find other ways to gather information. And, he says, with so much non-encrypted information being gathered on private citizens and consumers these days (such as GPS location, purchases, social media “likes” and contacts, web browsing habits), law enforcement still has plenty of investigative tools.

“End-to-end encryption is coming,” he says, pointing to Apple and to Facebook, which recently bought WhatsApp, a popular global messaging platform that is deploying strong encryption. “It will keep us more safe from criminals, from foreign spies, from prying eyes in general.”