At an event held during Apple’s fight with the FBI over whether it should help unlock a dead terrorist’s iPhone, CEO Tim Cook promised “We will not shrink” from the responsibility of protecting customer data —including from government overreach.

Yet the obvious next step for the company could be hard to take without inconveniencing customers.

Apple is currently able to read the contents of data stored in its iCloud backup service, something at odds with Cook’s claims that he doesn’t want his company to be capable of accessing customer data such as mobile messages.

Apple has not denied reports it is working to change that. And the company is expected to make some mention of its security technology at its World Wide Developers Conference next week, as it did at March’s iPhone event in March.

But redesigning iCloud so that only a customer can unlock his data would increase the risk of people irrevocably losing access to precious photos and messages when they lose their passwords. Apple would not be able to reset a customer’s password for them.

“That’s a really tough call for a company that says its products ‘Just work,’” says Chris Soghoian, a principal technologist with the American Civil Liberties Union—referring to a favorite line of Apple’s founder, Steve Jobs.

Cook has boasted of how the encryption built into Apple’s iPhones and iMessage system keeps people safe by ensuring that only they can access their data. FBI director James Comey has complained about it.

But the design of iCloud means that Apple can read much of its customers’ data, and help the government do so, too. The service is enabled by default (although you can opt out), and automatically backs up messages, photos, and more to the company’s servers. There the data is protected by encryption, which Apple has the key to unlock. The company’s standoff with the FBI happened only because the backups Apple handed the agency from San Bernardino shooter Syed Farook’s iPhone ended six weeks before the shooting, because he had turned them off.

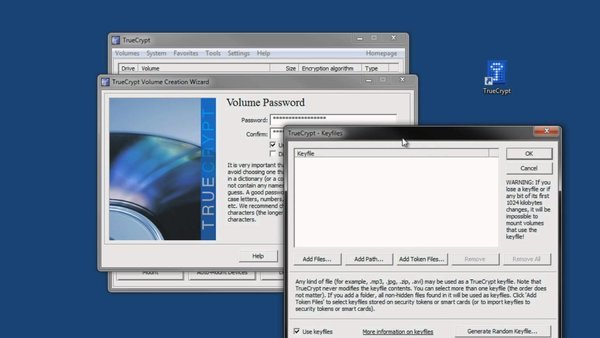

Apple could lock itself and law enforcement out of iCloud data by encrypting each person’s iCloud backups using a password under his control, perhaps the same one that locks his iPhone.

The company has not denied reports from the Financial Times and Wall Street Journal that it is working on such a design. Passwords and credit card details stored using an iCloud feature called Keychain are already protected in this way. But taking this approach would prevent Apple from being able to reset a person’s password if he forgets it. The data would be effectively gone forever.

It is probably impractical for Apple to roll out that approach for everyone’s data, as the company did for the security protections built into the iPhone, says Vic Hyder, chief strategy officer with Silent Circle, which offers secure messaging, calls, and data sharing for corporations.

“It puts control on the customer but also responsibility on the customer,” he says. “This will likely be an option, not the default.”

Soghoian of the ACLU agrees. “I think they will probably offer it as an option, but be reluctant to advertise that feature much,” he says. “More people forget their passwords than get investigated by the FBI.”

Bryan Ford, an associate professor at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne, says Apple could take steps to reduce the risk of accidental data loss.

The company’s FileVault disk encryption feature for PCs offers the option to print out a recovery key. A similar process could be used for iCloud encryption, says Ford.

Apple could also implement other safeguards, he says. For example, people could have the option of distributing extra encryption keys or passwords to several “trustees,” who could help recover data if the original password was lost. To prevent abuse it could be required that a certain number of trustees, say, three of five, came forward to unlock the data.

The cryptography needed for such a design is well understood, says Ford. He recently designed a similar but more complex system intended to help companies such as Apple prevent their software updates from being abused (see “How Apple Could Fed-Proof Its Software Update System”).

Alan Fairless, cofounder and CEO of SpiderOak, which offers companies fully encrypted data storage, says he thinks companies like Apple will eventually make truly secure cloud storage accessible to consumers.

Encrypted messaging was clunky and hard to use until recently, but is now widespread thanks to Apple and WhatsApp, he points out. Encrypting stored data is more challenging, but Apple has shown itself willing to spend significantly on encryption technology, for example by adding new chips to the iPhone, says Fairless.

However, he also thinks Apple and its customers aren’t yet ready for encrypted iCloud backups to be the default. “It’ll take consumer technology a while to catch up,” says Fairless.