Before the San Bernardino terror attack, Syed Rizawan Farook’s iPhone was just one fancy Apple device among hundreds of millions worldwide.

But since the California government worker and his wife shot and killed 14 people on December 2, apparently inspired by extremist group IS, his iPhone 5c has become a key witness – and the government wants Apple to make it talk.

The iPhone, WhatsApp, even social media – government authorities say some of tech fans’ favourite playthings are also some of the most powerful, and problematic, weapons in the arsenals of violent extremists.

Now, in a series of quiet negotiations and noisy legal battles, they’re trying to disarm them, as tech companies and civil liberties groups fight back.

The public debate started with a court order that Apple hack a standard encryption protocol to get at data on Farook’s iPhone, but its repercussions are being felt beyond the tech and law enforcement worlds.

“This is one of the harder questions that we will ever have to deal with,” said Albert Gidari, director of privacy at Stanford Law School’s Centre for Internet and Society.

“How far are we going to go? Where does the government power end to collect all evidence that might exist, and whether it infringes on basic rights? There’s no simple answer,” he told DPA.

It’s not new that terrorists and criminals use mainstream technology to plan and co-ordinate, or that law enforcement breaks into it to catch them. Think of criminals planning a robbery by phone, foiled by police listening in.

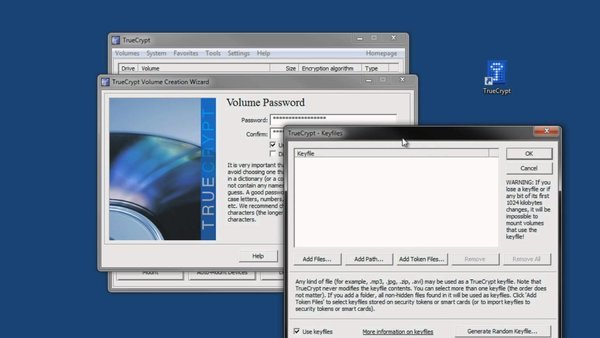

But as encryption technology and other next-generation data security move conversations beyond the reach of a conventional wiretap or physical search, law enforcement has demanded the industry provide “back-door” technology to access it too.

At the centre of the fray are otherwise mainstream gadgets and platforms that make private, secure and even anonymous data storage and communication commonplace.

Hundreds of millions of iPhones running iOS 8 or higher are programmed with the same auto-encryption protocol that has stymied investigators in the San Bernardino attack and elsewhere.

US authorities are struggling with how to execute a wiretap order on Facebook-owned WhatsApp’s encrypted messaging platform, used by 1 billion people, the New York Times reported.

In a similar case earlier this month, Brazilian authorities arrested a company executive for not providing WhatsApp data the company said it itself could not access.

Belgium’s interior minister Jan Jambon said in November he believed terrorists were using Sony’s PlayStation 4 gaming network to communicate, Politico reported, although media reports dispute his assertions.

In a world where much of social interaction has moved online, it’s only natural that violent extremism has made the move too.

ISIS, in particular, has integrated its real-world operations with the virtual world, using social media like Twitter and YouTube for recruitment and propaganda and end-to-end encryption for secure communication, authorities say.

Law enforcement authorities and government-aligned terror experts call it the “digital jihad”.

Under pressure from governments, social media providers have cracked down on accounts linked to extremists. Twitter reported it had closed 125,000 ISIS-linked accounts since mid-2015.

Most in the industry have drawn the line at any compromise on encryption, however, saying the benefits of secure data outweigh the costs of its abuse by criminals – leaving authorities wringing their hands.

“Something like San Bernardino” or the November 13 terror attack in Paris “can occur with virtually no indications it was about to happen,” retired general and former Obama anti-terror envoy John Allen warned an audience of techies at the South by Southwest digital conference.

Just a day before, US President Barack Obama had made an unprecedented appearance there, calling for compromise in the showdown between government and tech.

Citing examples of child pornographers, airline security and Swiss bank accounts, Obama said authorities must have the ability to search mobile devices, encrypted or not.

But Gidari called it a “Pandora’s box” too dangerous to open.