Was the Chattanooga shooter inspired by IS propaganda? There’s no evidence to back the claim, but some officials are already calling for access to encrypted messages and social media monitoring. Spencer Kimball reports.

It’s not an unusual story in America: A man in his 20s with an unstable family life, mental health issues and access to firearms goes on a shooting spree, shattering the peace of middle class life.

This time, the shooter’s name was Muhammad Youssef Abdulazeez, a Kuwaiti-born naturalized US citizen, the son of Jordanian parents of Palestinian descent. And he targeted the military.

Abdulazeez opened fire on a recruiting center and naval reserve facility in Chattanooga, Tennessee last Thursday. Four marines and a sailor, all unarmed, died in the attack.

But the picture that’s emerged from Chattanooga over the past several days is complicated, raising questions about mental health, substance abuse, firearms, religion and modernity.

Yet elected officials have been quick to suggest that events in Chattanooga were directly inspired by “Islamic State” (also known as ISIL or ISIS) Internet propaganda, though there’s still no concrete evidence to back up that claim.

“This is a classic lone wolf terrorist attack,” Senator Dianne Feinstein told US broadcaster CBS. “Last year, 2014, ISIL put out a call for people to kill military people, police officers, government officials and do so on their own, not wait for direction.”

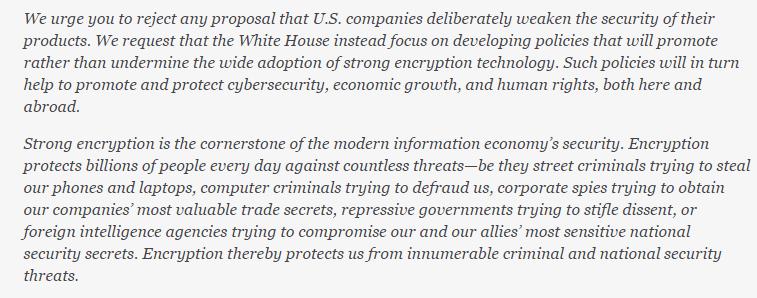

And according to Feinstein, part of the solution is to provide the government with greater access to digital communications.

“It is now possible for people, if they’re going to talk from Syria to the United States or anywhere else, to get on an encrypted app which cannot be decrypted by the government with a court order,” Feinstein said.

Going dark

Two years ago, former NSA contractor Edward Snowden revealed the extent of US government surveillance to the public. Responding to public outcry in the wake of the NSA revelations, companies such as Facebook, Yahoo, Google and others stepped up efforts to encrypt users’ personal data.

But the Obama administration, in particular FBI Director James Comey, has expressed growing concern about encryption technology. Law enforcement argues that even with an appropriate court order they still cannot view communications masked by such technology. They call it “going dark.”

Feinstein and others believe that Internet companies have an obligation to provide law enforcement with a way to view encrypted communications, if there’s an appropriate court order. But according to Emma Llanso, that would only create greater security risks.

“If you create a vulnerability in your encryption system, you are creating a vulnerability that can be exploited by any malicious actor anywhere in the world,” Llanso, director of the Free Expression Project at the Center for Democracy and Technology, told DW.

Monitoring social media

It’s not just an issue of encryption technology. There’s also concern about how militant groups such as the “Islamic State” are using social media, in particular Twitter.

“This is the new threat that’s out there over the Internet that’s very hard to stop,” Representative Michael McCaul told ABC’s This Week. “We have over 200,000 ISIS tweets per day that hit the United States.

“If it can happen in Chattanooga, it can happen anywhere, anytime, any place and that’s our biggest fear,” added McCaul, the chairman of the House Homeland Security committee.

In the Senate, an intelligence funding bill includes a provision that would require Internet companies to report incidents of “terrorist activity” on their networks to authorities.

According to Llanso, such activity isn’t defined anywhere in the provision, which means companies would have an incentive to overreport in order to meet their obligations. And speech clearly protected by the US First Amendment can also lead to incitement, said Philip Seib, co-author of “Global Terrorism and New Media.”

“If somebody puts something up on Facebook that says Muslims are being oppressed in the Western world, maybe that’s an incentive to somebody to undertake a violent act,” Seib told DW. “But you can’t pull that down, that is a free speech issue.”

Islamist connections?

In the case of Chattanooga, it’s unclear how government access to encrypted communications or requiring social media reporting would have stopped the shooting. One of Abdulazeez’s friends told CNN that the 24-year-old actually opposed the “Islamic State,” calling it a “stupid group” that “was completely against Islam.”

But Abdulazeez was critical of US foreign policy and expressed a desire to become a martyr in his personal writings, according to CNN sources. The young man’s father was put on a terrorist watch list but was then cleared of allegedly donating money to a group tied to Hamas. Abdulazeez also spent seven months in Jordan visiting family in 2014.

He also reportedly viewed content related to radical cleric Anwar al-Awlaki. An American citizen, Awlaki was killed in 2011 by a US drone strike in Yemen for alleged ties to al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula.

“The Guardian” reported that just hours before the shooting spree, Abdulazeez sent a text message to a friend with a verse from the Koran: “Whosoever shows enmity to a friend of Mine, then I have declared war against him.”

Guns, drugs and depression

Abdulazeez reportedly suffered from depression and had suicidal thoughts. He abused alcohol and drugs, including marijuana and caffeine pills. He had recently been arrested and charged with driving under the influence, with a court date set for July 30. He also took muscle relaxants for back pain and sleeping pills for a night shift at a manufacturing plant, according to the Associated Press.

His family life was also unstable. In 2009, Abdulazeez’s mother filed for divorce, accusing his father of abuse. The two later reconciled, according to the “New York Times.”

And he had access to guns, including an AK-47 assault rifle. Abdulazeez liked to go shooting and hunting. He also participated in mixed martial arts.

Officials told ABC News that Abdulazeez had conducted Internet research on Islamist militant justifications for violence, perhaps hoping to find religious atonement for his problems.

“The campaigns by the Western governments – the US primarily, the Brits and others – have indicated that they don’t really understand what’s going on in the minds of many young Muslims,” Seib told DW.

“The Western efforts don’t ring true amongst many people they seek to reach because on issues such as human rights the Western governments don’t have much credibility,” he added.