This story was delivered to BI Intelligence Apps and Platforms Briefing subscribers. To learn more and subscribe, please click here.

A French official plans to begin mobilizing a global effort — starting with Germany — against tech companies encrypting their messaging apps, according to Reuters.

Messaging apps, such as Telegram and WhatsApp, that promote end-to-end encryption, are used by terrorists to organize attacks in Europe, the minister said. Although individual governments have previously explored seeking mandatory backdoors from tech companies, this is the first attempt to unify the case across countries. If successful, it could make it more difficult for these companies to resist the requests.

The debate over the use of end-to-end encryption in chat apps recently made headlines after it was revealed that terrorists might have used secure chat apps to coordinate a slew of attacks in France. Law-enforcement officials argue that the highly secure tech impedes their ability to carry out investigations relating to crimes that use the chat apps.

Tech companies argue that providing backdoor access to their apps, even to governments, creates a potential vulnerability that can be targeted by malicious players seeking access to users’ personal data. To add weight to this argument, it was revealed last week that a “golden key” built by Microsoft for developers was accidentally leaked. And while the company has sent out patches for a majority of its devices, it’s unlikely to reach those potentially affected.

BI Intelligence, Business Insider’s premium research service, has compiled a detailed report on messaging apps that takes a close look at the size of the messaging app market, how these apps are changing, and the types of opportunities for monetization that have emerged from the growing audience that uses messaging services daily.

Here are some of the key takeaways from the report:

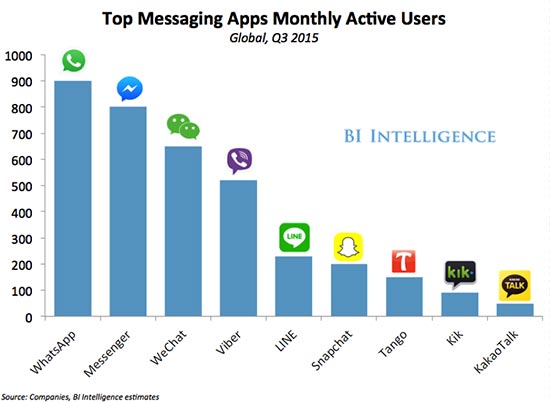

- Mobile messaging apps are massive. The largest services have hundreds of millions of monthly active users (MAU). Falling data prices, cheaper devices, and improved features are helping propel their growth.

- Messaging apps are about more than messaging. The first stage of the chat app revolution was focused on growth. In the next phase, companies will focus on building out services and monetizing chat apps’ massive user base.

- Popular Asian messaging apps like WeChat, KakaoTalk, and LINE have taken the lead in finding innovative ways to keep users engaged. They’ve also built successful strategies for monetizing their services.

- Media companies, and marketers are still investing more time and resources into social networks like Facebook and Twitter than they are into messaging services. That will change as messaging companies build out their services and provide more avenues for connecting brands, publishers, and advertisers with users.

In full, this report:

- Gives a high-level overview of the messaging market in the US by comparing total monthly active users for the top chat apps.

- Examines the user behavior of chat app users, specifically what makes them so attractive to brands, publishers, and advertisers.

- Identifies what distinguishes chat apps in the West from their counterparts in the East.

- Discusses the potentially lucrative avenues companies are pursuing to monetize their services.

- Offers key insights and implications for marketers as they consider interacting with users through these new platforms.