In a “60 Minutes” appearance Sunday, Apple CEO Tim Cook reiterated his support of encryption, in the face of renewed criticism from the U.S. intelligence community that these digital locks interfere with the ability to detect threats to national security.

Cook used an interview with CBS’s Charlie Rose to lay out his argument for why weakening encryption on consumer devices is a bad idea.

“If there’s a way to get in, then somebody will find the way in,” Cook said. “There have been people that suggest that we should have a back door. But the reality is if you put a back door in, that back door’s for everybody, for good guys and bad guys.”

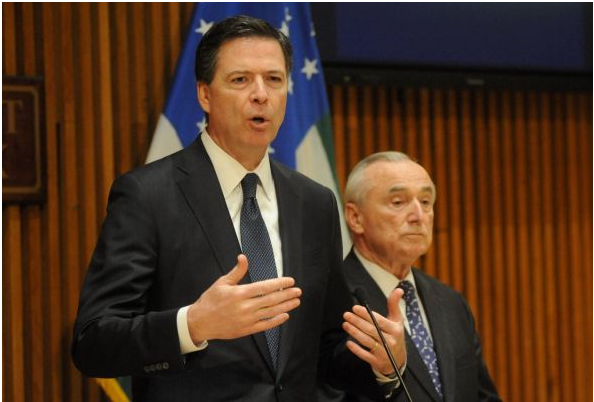

Following the mass murders in Paris and San Bernardino, Apple and other technology companies have come under mounting pressure to give U.S. law enforcement access to their consumers’ encrypted messages. FBI Director James Comey complained that potential attackers are using communications platforms that authorities can’t access — even through warrants and wiretaps.

“I don’t believe that the trade-off here is privacy versus national security,” Cook said in the interview. “I think that’s an overly simplistic view. We’re America. We should have both.”

Cook said modern smartphones such as the iPhone contain sensitive information: Personal health details, financial data, business secrets and intimate conversations with family, friends or co-workers. The only way to ensure this information is kept secure is to encrypt it, turning personal data into indecipherable garble that can only be read with the right key — a key that Apple doesn’t hold.

Apple will comply with warrants seeking specific information, Cook said, but there’s only so much it can provide.

Moving to other topics, Cook defended Apple’s tax strategy, which has drawn criticism from Congress. He described as “total political crap” charges that Apple is engaged in an elaborate scheme to pay little or no taxes on overseas income. He also discussed the company’s use of one million Chinese workers to manufacture most of its products, saying they possess the skills that American workers now lack.

“The U.S., over time, began to stop having as many vocational kind of skills,” Cook said in the interview. “I mean, you can take every tool and die maker in the United States and probably put them in the room that we’re currently sitting in. In China, you would have to have multiple football fields.”

The television news magazine also took viewers on a tour of Apple’s headquarters. Rose talked with design guru Jony Ive about the Apple Watch inside the secret design studio, where the wooden tables were draped with covers to shield future projects from the camera.

Retail chief Angela Ahrendts escorted Rose to a mock Apple Store in an unmarked warehouse off the main Cupertino campus.

And, armed with cameras and drones, Rose ascended a giant mound of earth to visit to the site of Apple’s future corporate headquarters, a building dubbed the “spaceship” by many. The $5 billion project, with 7,000 trees, fruit and vegetable gardens and natural ventilation system, is expected to one day house 13,000 employees.