In the second installment of a thought piece about end-to-end encryption and its effect on national security, Lawfare editor-in-chief Benjamin Wittes and co-author Zoe Bedell hypothesize a situation in which Apple is called upon to provide decrypted communications data as part of a legal law enforcement process.

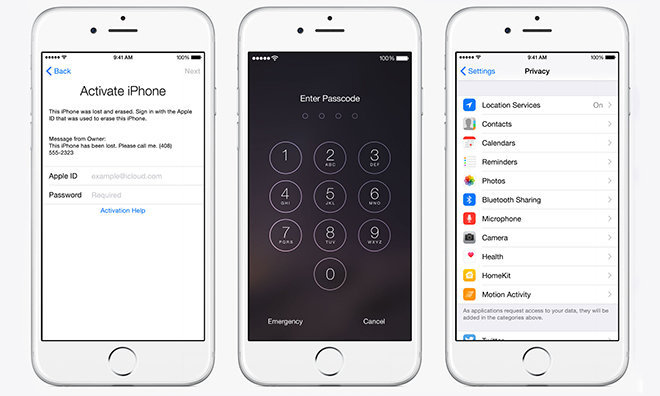

Since Apple does not, and on devices running iOS 8 cannot, readily hand over decrypted user data, a terrorist might leverage the company’s messaging products to hide their agenda from government security agencies. And to deadly effect.

As The Intercept reported, the hypotheticals just made the ongoing government surveillance versus consumer protection battle “uglier.”

Wittes and Bedell lay out a worst case scenario in which an American operative is recruited by ISIS via Twitter, then switches communication methods to Apple’s encrypted platform. The person might already be subject to constant monitoring from the FBI, for example, but would “go dark” once they committed to iOS. Certain information slips through, like location information and metadata, but surveillance is blind for all intents and purposes, the authors propose. The asset is subsequently activated and Americans die.

Under the civil remedies provision of the Antiterrorism Act (18 U.S. Code §2333), victims of international terrorism can sue, Lawfare explains, adding that an act violating criminal law is required to meet section definitions. Courts have found material support crimes satisfy this criteria. Because Apple was previously warned of potential threats to national security, specifically the danger of loss of life, it could be found to have provided material support to the theoretical terrorist.

The authors point out that Apple would most likely be open liability under §2333 for violating 18 USC §2339A, which makes it a crime to “provide[] material support or resources … knowing or intending that they are to be used in preparation for, or in carrying out” a terrorist attack or other listed criminal activity. Communications equipment is specifically mentioned in the statute.

Ultimately, it falls to the court to decide liability, willing or otherwise. Wittes and Bedell compare Apple’s theoretical contribution to that of Arab Bank’s monetary support of Hamas, a known terrorist organization. The judge in that case moved the question of criminality to Hamas, the group receiving assistance, not Arab Bank.

“The question for the jury was thus whether the bank was secondarily, rather than primarily, liable for the injuries,” Wittes and Bedell write. “The issue was not whether Arab Bank was trying to intimidate civilians or threaten governments. It was whether Hamas was trying to do this, and whether Arab Bank was knowingly helping Hamas.”

The post goes on to detail court precedent relating to Apple’s hypothetical case, as well as legal definitions of what constitutes criminal activity in such matters. Wittes and Bedell conclude, after a comprehensive rundown of possible defense scenarios, that Apple might, in some cases, be found in violation of the criminal prohibition against providing material support to a terrorist. They fall short of offering a viable solution to the potential problem. It’s also important to note that other companies, like Google and Android device makers, proffer similar safeguards and would likely be subject to the same theoretical — and arguably extreme — interpretations of national policy described above.

Apple has been an outspoken proponent of customer data privacy, openly touting strong iOS encryption and a general reluctance to handover information unless served with a warrant. The tack landed the company in the crosshairs of law enforcement agencies wanting open access to data deemed vital to criminal investigations.

In May, Apple was one of more than 140 signatories of a letter asking President Barack Obama to reject any proposals that would colorably change current policies relating to the protection of user data. For example, certain agencies want Apple and others to build software backdoors into their encrypted platforms, a move that would make an otherwise secure system inherently unsafe.