Hot on the heels of Canberra’s successful push for mandatory retention of telco records about who we call, and how much we web surf, and when we email, we sense a new debate about technologies that scramble the actual contents of our communications, so an investigator may be able to work out who we called or mailed, but never what was said or written.

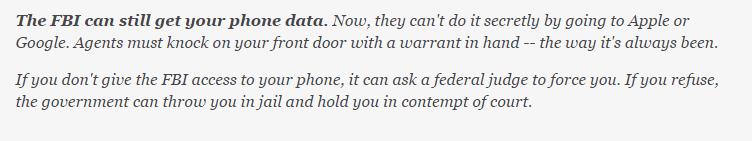

Recent media articles have noted that the New South Wales Crime Commission has been hindered by phone systems that encrypt conversations that prevent a crime fighter from eavesdropping. While the new data retention laws may alert Batman to the fact that Joker and Penguin have been trading a lot of calls lately, and Commissioner Gordon might be more than willing to authorise a bat-intercept on the strength of that information, the chase comes to naught when the caped crusader’s phone tap reveals nothing more than gibberish on the line.

As Fairfax Media also reports, drug dealers and money launderers are using Phantom Secure, an encryption tool for Blackberry messages, and BlackPhones, a voice encrypter for Android phones, to communicate in code. No doubt terrorists are customers for the same technologies. So, just months after the national parliament reached an accord on mandatory requirements for communications companies to retain details about our calls, messages and web surfing, do we need to decide the even thornier questions of whether a ban on certain voice and data encryption tools is possible and, if so, whether it would be the right thing to do?

That’s a key difference between the existing so-called metadata retention law and any move against products like Phantom Secure and BlackPhone.All the retention law does, and even this much is highly contentious from a civil liberties perspective, is requires comms companies to keep certain transactional records.

A law dealing with encryption technologies would need to go much further, criminalising hardware, software and services that are already in common use including, as New South Wales police readily agree, by legitimate businesses. Mind you, as the human rights movement would point out, you needn’t be a business to have a right to communicate privately.

What might an anti-encryption law look like? 99 per cent of all encryption would have to be excepted. Every time we visit an authenticated website, or buy online using a bank or quasi-bank like Paypal, we unknowingly use automated encryption. These communications are scrambled on their way across the internet, but they begin and end language, and an appropriately authorised regulator that wants to know what information was exchanged can get their hands on it. This isn’t the kind of encryption that investigators need to worry about.

AN ENCRYPTION LICENCE?

One option is a law requiring users of high strength encryption tools to be licensed, like gun owners need a licence. Before guffawing at such a thought, be aware that this is how Team America tried to deal with the issue internationally. The first mass market, effectively unbreakable text encryption tool was called PGP, standing for Pretty Good Privacy. The acronym was an in-joke. The developers knew how good their solution was, and gave it a name that was like calling Adam Gilchrist PGC, a Pretty Good Cricketer.

PGP wasn’t restricted within the USA itself. They have a constitutional right of free speech. But anyone involved in unlicensed export to other countries committed a criminal offence against, believe it or not, a law against unauthorised sale of munitions. That was thirty years ago, and the discussion we may now be about to have about drug runners, money launderers and terrorists will cross ground that was well traversed back then.

Why should we let people we don’t trust access technologies that facilitate conversations that might be against our interests and that we can’t intercept no matter how reasonable our suspicions and how high the stakes?

The problem with that approach in 2015 is that any solution that compromises the rights to free or private speech and the presumption of innocence, and criminalises or licenses existing freedoms, should ring every alarm and flash every red light a modern democracy has to ring and flash.

If drug runners, money launderers and their ilk are using encryption tools, by all means let’s deal with that in a targeted, measured way. But let’s also never forget the thanks the developer of PGP once received from a dissident behind the Iron Curtain, for serving freedom and saving lives.