When the FBI said it couldn’t unlock the iPhone at the center of the San Bernardino shooting investigation without the help of Apple, the hackers at DriveSavers Data Recovery took it as a challenge.

Almost 200 man hours and one destroyed iPhone later, the Bay Area company has yet to prove the FBI wrong. But an Israeli digital forensics firm reportedly has, and the FBI is testing the method.

Finding a solution to such a high-profile problem would be a major feat — with publicity, job offers and a big payday on the line. But, in fact, the specialists at DriveSavers are among only a few U.S. hackers trying to solve it. Wary of the stigma of working with the FBI, many established hackers, who can be paid handsomely by tech firms for identifying flaws, say assisting the investigation would violate their industry’s core principles.

Some American security experts say they would never help the FBI, others waver in their willingness to do so. And not all of those who would consider helping want their involvement publicized for risk of being labeled the hacker who unhinged a backdoor to millions of iPhones.

“The FBI has done such a horrible job of managing this process that anybody in the hacking community, the security community or the general public who would openly work with them would be viewed as helping the bad guys,” said Adriel Desautels, chief executive of cybersecurity testing company Netragard. “It would very likely be a serious PR nightmare.”

Much of the security industry’s frustration with the FBI stems from the agency’s insistence that Apple compromise its own security. The fact that the FBI is now leaning on outside help bolsters the security industry’s belief that, given enough time and funding, investigators could find a workaround — suggesting the agency’s legal tactics had more to do with setting a precedent than cracking the iPhone 5c owned by gunman Syed Rizwan Farook.

Some like Mike Cobb, the director of engineering at DriveSavers in Novato, Calif., wanted to be the first to find a way in. Doing so could bring rewards, including new contracts and, if desired, free marketing.

“The bragging rights, the technical prowess, are going to be considerable and enhanced by the fact that it’s a very powerful case in the press,” said Shane McGee, chief privacy officer for cybersecurity software maker FireEye Inc.

Altruism could motivate others. Helping the FBI could further an inquiry into how a husband-and-wife couple managed to gun down 14 people, wound many others and briefly get away.

Another positive, McGee said, is that legal liability is low: While unauthorized tampering with gadgets has led to prison time, it’s legal as long as people meddle with iPhones they own — and the court order helps too.

But top security experts doubt the benefits are worth the risk of being seen as a black sheep within their community.

Hackers have said they don’t want to touch the San Bernardino case “with a 10-foot pole because the FBI doesn’t look the like good guy and frankly isn’t in the right asking Apple to put a back door into their program,” Desautels said. The assisting party, if ever identified, could face backlash from privacy advocates and civil liberties activists.

“They’d be tainted,” Desautels said.

The unease in the hacker community can be seen through Nicholas Allegra, a well-known iPhone hacker who most recently worked for Citrix.

Concerned an FBI victory in its legal fight with Apple would embolden authorities to force more companies to develop software at the government’s behest, Allegra had dabbled in finding a crack in iPhone 5c security. If successful, he hoped his findings would lead the FBI to drop the Apple dispute.

But he has left the project on the back burner, concerned that if he found a solution, law enforcement would use it beyond the San Bernardino case.

“I put in some work. I could have put more in,” he said. But “I wasn’t sure if I even wanted to.”

Companies including Microsoft, United Airlines and Uber encourage researchers and even hackers to target them and report problems by dangling cash rewards.

HackerOne, an intermediary for many of the companies, has collectively paid $6 million to more than 2,300 people since 2013. Boutique firms and freelancers can earn a living between such bounties and occasionally selling newly discovered hacking tools to governments or malicious hackers.

But Apple doesn’t have a bounty program, removing another incentive for tinkering with the iPhone 5c.

Still, Israeli firm Cellebrite is said to have attempted and succeeded at defeating the device’s security measures.

The company, whose technology is heavily used by law enforcement agencies worldwide to extract and analyze data from phones, declined to comment. The FBI has said only that an “outside party” presented a new idea Sunday night that will take about two weeks to verify. Apple officials said they aren’t aware of the details.

Going to the FBI before going to the company would violate standard practice in the hacking community. Security researchers almost always warn manufacturers about problems in their products and services before sharing details with anyone else. It provides time for a issuing a fix before a malicious party can exploit it.

“We’ve never disclosed something to the government ahead of the company that distributed the hardware or software,” McGee said. “There could be far-reaching consequences.”

Another drawback is that an iPhone 5c vulnerability isn’t considered a hot commodity in the minds of many hackers, who seek to one-up each other by attacking newer, more widely used products. The 5c model went on sale in 2013 and lacks a fingerprint sensor. Newer iPhones are more powerful and have different security built into them. Only if the hack could be applied to contemporary iPhones would it be worth a rare $1-million bounty, experts say.

The limited scope of this case is why many hackers were taken back by a court order asking for what they consider broadly applicable software to switch off several security measures. Instead, experts wanted the FBI to invest in going after the gunman’s specific phone with more creativity. In other words, attack the problem with technology, not the courts.

“If you have access to the hardware and you have the ability to dismantle the phone, the methodology doesn’t seem like it would be all that complex,” Desautels said.

Two years ago, his team tried to extract data from an iPad at the request of a financial services company that wanted to test the security of the tablets before offering them to employees. Netragard’s researcher failed after almost a month; he accidentally triggered a date change within the software that rendered the iPad unusable. But Desautels said cracking the iPad would have been “possible and trivial” for someone with more time and a dozen iPads to mess with.

The same, he imagines, would be true for an iPhone. The FBI, though, has said it had exhausted all known possibilities.

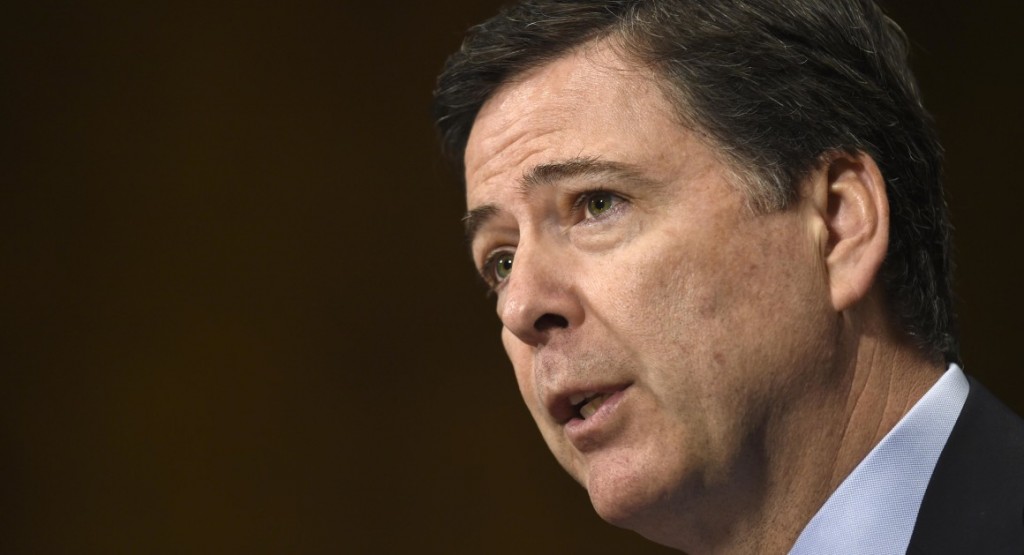

Taking Apple to court generated attention about the problem and “stimulated creative people around the world to see what they might be able to do,” FBI Director James Comey said in a letter to the Wall Street Journal editorial board Wednesday. Not “all technical creativity” resides within government, he said.

The plea worked, grabbing the interest of companies like DriveSavers, which gets about 2,000 gigs a month to retrieve photos, videos and notes from phones that are damaged or belong to someone who died. But despite all of the enticements in the San Bernardino case, they’ve worked to unlock an iPhone 5c only intermittently.

They’ve made progress. Cobb’s team can spot the encrypted data on an iPhone 5c memory chip They’re exploring how to either alter that data or copy it to another chip. Both scenarios would allow them to reset software that tracks invalid password entries. Otherwise, 10 successive misfires would render the encrypted data permanently inaccessible.

Swapping chips requires soldering, which the iPhone isn’t built to undergo multiple times. They have an adapter that solves the issue, and about 300 old iPhones in their stockpile in case, as one already has, the device gets ruined.

Had they been first to devise a proposed solution, DriveSavers “absolutely” would have told the FBI because their method doesn’t present extraordinary security risks, Cobb said.

But whether it would want to be publicly known as the code cracker in the case, Cobb said that would be “a much bigger, wider conversation” to ponder.