Facebook’s native chat is due to be silenced: Facebook’s reportedly going to kill it off, forcing users to instead use Messenger.

Rumor has it that Facebook Messenger will also offer the option of end-to-end encryption sometime in the next few months.

The Guardian, relying on input from three unnamed sources close to the project, earlier this week reported the end-to-end encryption news. Facebook hasn’t confirmed it, declining to comment on rumors or speculation.

The timing of these two things isn’t clear, but it would make sense for them to coincide – kill the native chat app just as a more privacy-protecting version of Messenger is ready to pull users in.

Ars Technica reports that some users are already getting pushed off the mobile version of Facebook’s native chat and onto the free, dedicated Messenger app.

Users of the regular Facebook mobile app were evicted a while ago. Now, it’s happening to those who access it via their phones’ web browsers or via third-party apps such as Tinfoil or Metal, Ars reports.

Some Android users are even being booted off chat automatically, shunted over to Google’s Play store to download Messenger when they try to check out their messages on the mobile site.

End-to-end encryption would shield conversations from all but the sender and receiver. That includes the prying eyes of both government surveillance outfits or from tech companies themselves.

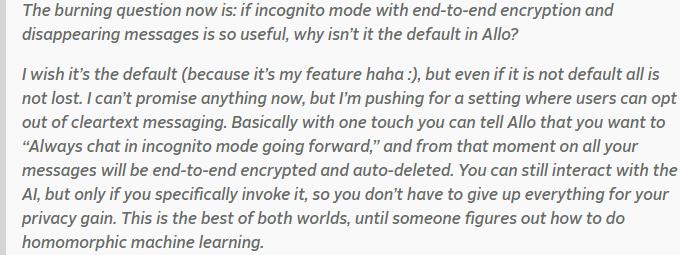

The tradeoff: if Facebook can’t see conversations or get at users’ personal data, it can’t use artificial intelligence (AI) to chime in and do helpful things.

And, as we reported yesterday, Facebook’s on track to do a lot more language processing to figure out, for example, who’s messaging about needing a ride and therefore might want to have an Uber link pop up.

End-to-end encryption in Messenger would also put it on par with other encrypted messaging apps, including Apple iMessage, WhatsApp and Google’s new Allo messaging app.

Both Facebook and Google are trying to balance users’ demands for secure messaging with their thirst for services enhanced by the use of users’ personal data. Their solution: offer the end-to-end encryption as an opt-in feature.

As you might expect, some users are displeased with the notion of being forced onto Messenger, while some privacy experts are displeased with the idea that the speculated end-to-end encryption is opt-in rather than default.

The Guardian quoted Kenneth White, a security researcher and co-director of the Open Crypto Audit Project, which tests the security of encryption software:

The timing on killing native chat and releasing the Messenger crypto feature isn’t known, but The Register reports that it’s already been released for Windows 10 Mobile users.