Google is disclosing how much of the traffic to its search engine and other services is being protected from hackers as part of its push to encrypt all online activity.

Encryption shields 77 percent of the requests sent from around the world to Google’s data centers, up from 52 percent at the end of 2013, according to company statistics released Tuesday. The numbers cover all Google services except its YouTube video site, which has more than 1 billion users. Google plans to add YouTube to its encryption breakdown by the end of this year.

Encryption is a security measure that scrambles transmitted information so it’s unintelligible if intercepted by a third party.

Google began emphasizing the need to encrypt people’s online activities after confidential documents leaked in 2013 by former National Security Agency contractor Edward Snowden revealed that the U.S. government had been vacuuming up personal data transferred over the Internet. The surveillance programs exploited gaping holes in unencrypted websites.

While rolling out more encryption on its services, Google has been trying to use the clout of its influential search engine to prod other websites to strengthen their security.

In August 2014, Google revised its secret formula for ranking websites in its search order to boost those that automatically encrypted their services. The change meant websites risked being demoted in Google’s search results and losing visitors if they didn’t embrace encryption.

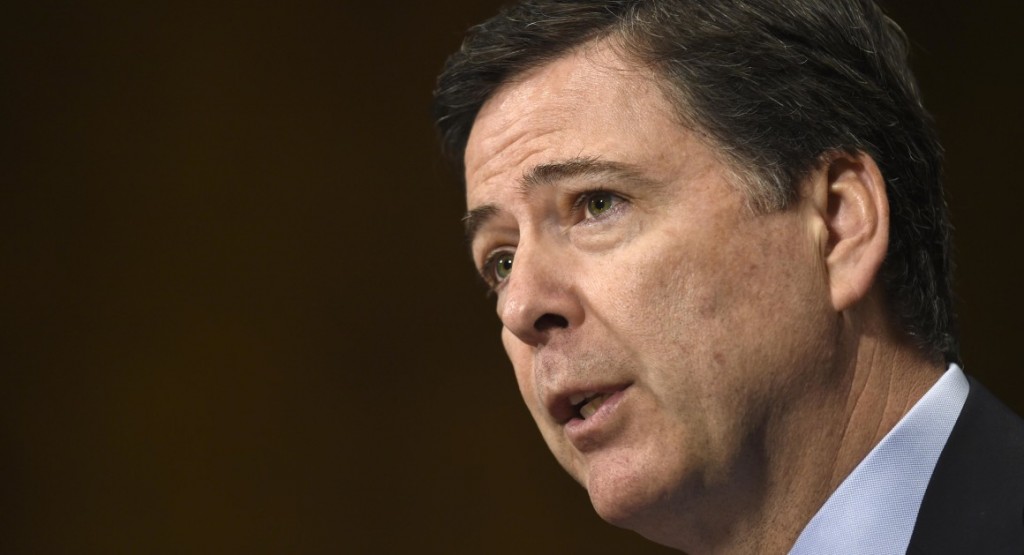

Google is highlighting its own progress on digital security while the FBI and Apple Inc. are locked in a court battle over access to an encrypted iPhone used by one of the two extremist killers behind the mass shootings in San Bernardino, California, in December.

Google joined several other major technology companies to back Apple in its refusal to honor a court order to unlock the iPhone, arguing that it would require special software that could be exploited by hackers and governments to pry their way into other encrypted devices.

In its encryption crusade, Google is trying to make it nearly impossible for government spies and other snoops from deciphering personal information seized while in transit over the Internet.

The statistics show that Google’s Gmail service is completely encrypted as long as the correspondence remains confined to Gmail. Mail exchanges between Gmail and other email services aren’t necessarily encrypted.

Google’s next most frequently encrypted services are maps (83 percent of traffic) and advertising (77 percent, up from just 9 percent at the end of 2013). Encryption frequency falls off for Google’s news service (60 percent) and finance (58 percent).