THE revelations from former US National Security Agency (NSA) contractor Edward Snowden that the US Government has been tapping communications have created greater awareness on the need for secure communications, which in turn has given rise to secure messaging apps such as Telegram, Wickr and Threema.

Privacy should not be a concern for just individuals, but businesses also need to be aware of how tapped communications can affect them, according to Maxim Glazov (pic above), chief executive officer of Singapore-based SafeChats.

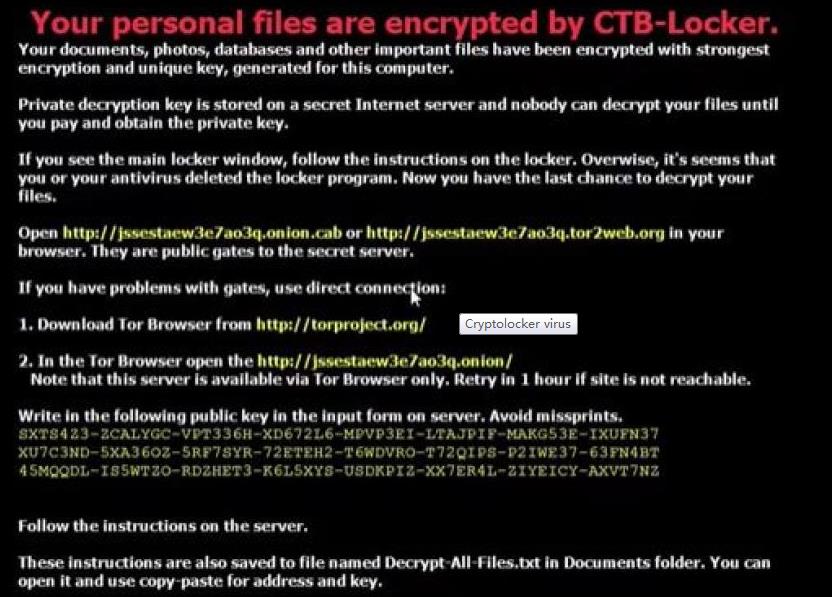

For example, customers’ VoIP (Voice-over-Internet Protocol) calls can be intercepted and sensitive information gathered for blackmail. Hackers can gain unauthorised access to a customer’s webmail account to forge emails, and issue payment instructions to send the money to the hackers’ accounts instead.

The scenario is made worse by the fact that many businesses use unsecured mass-market services because of their ease of use.

It was this realisation that catalysed Glaznov and his chief technology officer Nikita Osipov to build SafeChats, which they claim is a secure communications platform that protects collaboration as well.

The company was one of the finalists at the recent RSA Conference Asia Pacific and Japan (RSAC APJ) Innovation Sandbox startup competition in Singapore.

SafeChat began as an internal project for an undisclosed international logistics and finance company that Osipov and Glaznov were part of, looking into the problem of communicating sensitive information with customers more securely and efficiently than existing methods.

Glaznov’s initiative to build a secure communication platform got traction with his customers which were eager to use the platform for themselves

The market for secure communication, whether for consumers or enterprises, is gaining traction with the entry of companies like Silent Circle, Tigertext and ArmourText.

Osipov recognises the growing maturity of the market but remains undeterred. “We keep ourselves motivated by acquiring more use cases for what is essentially a red-ocean market, and the constant validation that there is a need for such a communications platform.”

The SafeChats platform aims to encompass the entire suite of communications, from email to messaging, and from file transfers to video and voice calls. It also gives the option of using the customer’s own server infrastructure instead of SafeChats’.

“SafeChats is the only secure communications platform that also integrates collaborative features and a full suite of privacy features,” Osipov claimed.

The SafeChats messaging volume has grown 10 times in the last six months, organically from initial customers, without an official release, the startup claimed.

When asked about its customers, Osipov cryptically replied, “As a company entrenched in security and privacy, we cannot reveal our current client list … and there are some users on board that we simply don’t know who they are.”

The company’s revenue model is set to be freemium Software-as-a-Service, with different tiers of control and fees being charged for white labeling and on-premises installation.

It also charges enterprise customers on a per-user if they “enforce a security policy on employees or create groups of more than 15 individuals,” Osipov said.

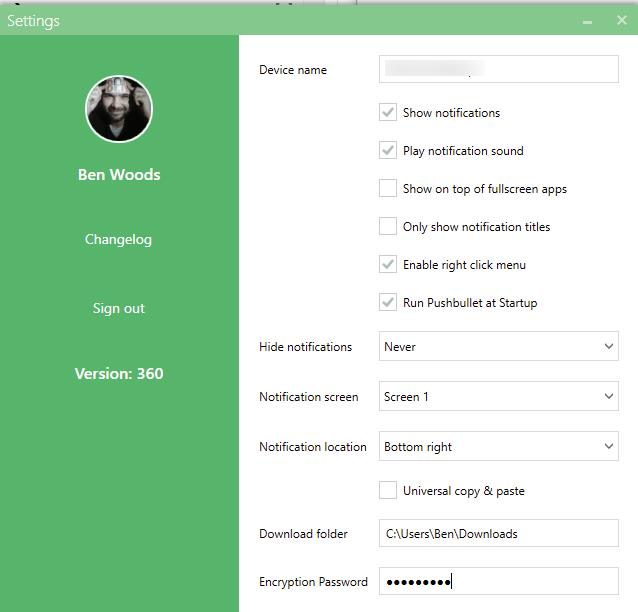

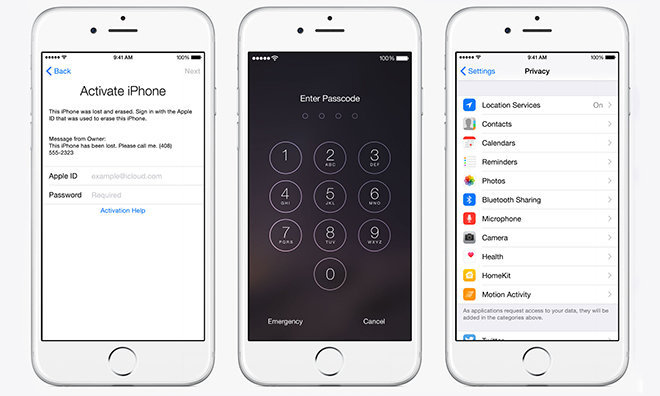

SafeChats is currently in public beta and will be officially launched at the end of August. It is currently available for the iOS and Android platforms. There are plans to make a desktop version for Mac OS X and Windows.

The challenges

Spinning off into its own startup has seen some challenges, with Osipov (pic above) saying that one main one was building the right team.

“Once you have a great team, everything becomes so much easier,” he said.

On the technical front, coming up with the right set of technologies to use was one of the biggest challenges.

“We evaluated multiple different software solutions, protocols and algorithms that we could use before we settled on the current architecture,” said Osipov.

“All that required extensive research work – thinking of the whole system from the technical side and possible technical challenges in the future … and how to solve them … [while making sure] it remains very easy to use,” he added.

Under the hood

SafeChats uses a variety of encryption algorithms, depending on the particular function.

“We use well-known end-to-end encryption algorithms trusted by security experts as the core of our platform, which means that your data stays safe in transit and only you and the intended recipient have access to it,” Osipov said. For instant messaging, it uses Off-the-Record messaging (OTR) and the socialist millionaire protocol. OTR messaging uses a combination of Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) algorithms with a 128-bit key strength, with a public key exchange protocol for authentication. The socialist millionaire protocol allows two parties to verify each other’s identity through a shared secret.

For voice calls and file transfers, SafeChats uses an AES 256-bit key, military-grade encryption to protect data and calls.

Future plans

SafeChats started as a bootstrapped startup, and is now on the lookout for investors who will be more than just people writing cheques.

“We are on the lookout for investors with the capacity to be strategic partners and who can provide channels for the product and its derivatives,” Osipov said.

SafeChats will be seeking pre-Series A round within the next six months, and is looking to raise over US$700,000, aiming for a valuation of US$6 million.

It intends to expand the team, especially on the marketing and technical fronts, the latter including 24/7 support.

And it will beef up its software development team “to work on enterprise features like integration with third-party services and advanced authentication options like two-factor authentication (2FA) using software and hardware tokens,” Osipov said.

Beyond expanding the platforms SafeChats works on, the company is also working on integrating the platform with other software and hardware solutions to utilise its end-to-end encryption. This will secure other software solutions as well as pave the way for Internet of Things (IoT) security.

“We won’t announce any names for now as there are many legal issues involved in this sort of integration, and with providing official software developer kits to everyone,” Osipov said.

“All we can say at the moment is that you can be sure that most popular software and hardware solutions will work with SafeChats,” he declared.

The company wants to open up its Application Program Interface (API) to others so that they can work on their own integrations as well, bringing the SafeChats level of security to other software.

“We also hope to form a community of developers to implement future integrations so everyone benefits,” Osipov claimed.