A new surveillance proposal in the United Kingdom is drawing criticism from privacy advocates and tech companies that say it gives the government far-reaching digital surveillance powers that will affect users outside the nation’s borders.

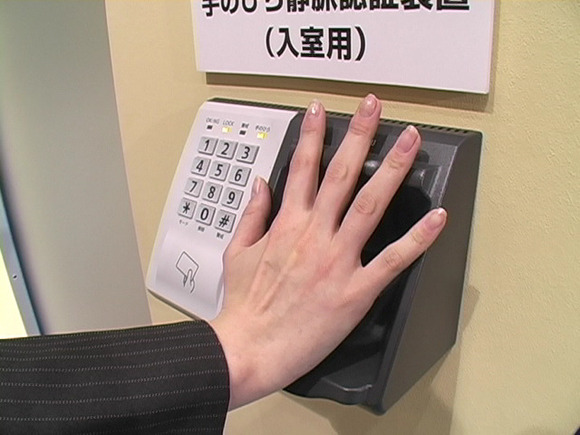

The Draft Investigatory Powers Bill released by British Home Secretary Theresa May Wednesday would force tech companies to build intercept capabilities into encrypted communications and require telecommunications companies to hold on to records of Web sites visited by citizens for 12 months so the government can access them, critics allege.

Policy changes are necessary to maintain security in a changing digital landscape, the government argued. “The means available to criminals, terrorists and hostile foreign states to co-ordinate, inspire and to execute their plans are evolving,” May wrote in a forward to the bill. “Communications technologies that cross communications platforms and international borders increasingly allow those who would do us harm the opportunity to evade detection.”

The bill has some new judicial oversight mechanisms, but the response from privacy advocates was largely negative, with some arguing that those changes aren’t enough to compensate for the expanse of new powers.

“The law would apply to all companies doing business with the UK, which includes basically all companies that operate over the internet,” said Nathan White, senior legislative manager at digital rights group Access. “This means that even wholly domestic encrypted communications in the United States, France, or South Africa would be put at risk.”

Some tech companies themselves also raised alarm bells. “Many aspects of the draft Bill would directly impact internet users not just in the UK, but also beyond British borders,” Yahoo said in a blog post. “Of most concern to us at this stage is the UK Government’s proposal to affirm extraterritorial jurisdiction over foreign service providers.”

The U.K. government says some of the controversial aspects of the draft, including the requirement to unlock encrypted communications, date back to laws already on the books and it replaces a patchwork of powers which go back to the early days of the Web. However, while a Code of Conduct for Interception Capabilities released by the British government earlier this year said communications companies were required to maintain a “permanent interception capability,” it made no mention of decrypting such content.

Privacy advocates say the government is reinterpreting earlier laws in problematic ways. “This is a major change” that would effectively outlaw end-to-end encryption, a form of digital security where only the sender and the recipient of a message can unlock it, White said.

In meetings before the draft was released, the government pressed at least one tech company to build in backdoors into encrypted communications, according to a person familiar with the issue who requested anonymity because he was not authorized to comment on the issue.

Apple’s iMessage system uses end-to-end encryption as do an increasingly number of standalone messaging and calling apps including Signal. If the proposal becomes law, critics warn, such services may be forced to alter their systems to include such “backdoors” to allow the government to access encrypted content — something encryption experts say would undermine security by making the underlying code more complex and giving hackers something new to target — or exit the market. Apple declined to comment on the bill, but chief executive Tim Cook has been a vocal opponent of government-mandated backdoors in the past.

Encryption was at the heart of a U.S. policy debate over the last year. The dialogue was triggered when Apple moved to automatically protect iOS devices with encryption so secure the company itself cannot unlock data stored on an iPhone even if faced with a warrant, assuming that a user turns off automatic back-ups to the company’s servers.

Some law enforcement officials warn that criminals and terrorists are “going dark” due to such technology. But the Obama administration decided not to press for a legislative mandate that would require companies to build ways to access such content into their products, although it has not yet come out with a full policy position on the issue.

Critics argue that has led to ambiguity which emboldened British officials. “This draft proposal from the U.K. government demonstrates the lack of leadership on encryption policy from the Obama Administration” and could lead to similar proposals in other parts of the world, said White.

If one country is able to force companies to unlock encrypted data it will be hard to fend off such requests from others including China and Russia, some inside tech companies fear.

When asked about the British proposal by The Post, National Security Council spokesperson Mark Stroh declined to weigh in. “We’d refer you to the British government on draft British legislation,” he said via e-mail.