Despite the lack of evidence, the Obama Administration has revived the encryption debate, pointing to encryption as an aid to the terrorists behind the Nov. 13 Paris attacks.

Investigators from France and the U.S. have conceded that there has been no evidence backing up their conclusion that the terrorist behind the attacks relied on the latest, high-level encryption techniques being offered to consumers by Google and Apple.

Yet, the debate over government-grieving encryption is back in high gear.

Decrypting the Encryption Debate

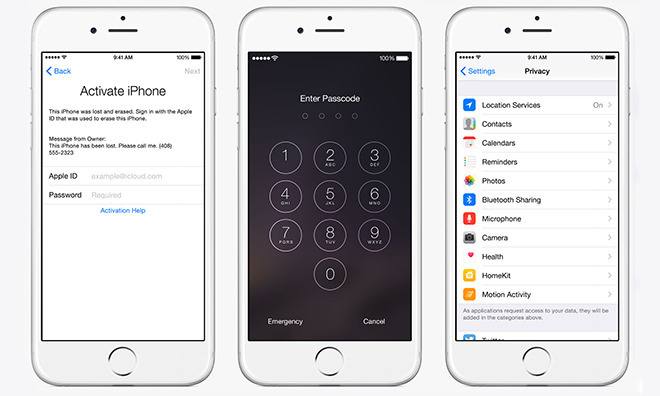

The Great Encryption debate kicked into full swing about a year ago, when current and former chiefs of the U.S. Department of Justice began calling on Apple and Google to create backdoors in iOS 8 and Android Lollipop.

The encryption built for the two mobile operating systems is so tough, that the world’s best forensic scientists in all of computing wouldn’t be able to crack devices running the software in time for a seven-year statute of limitations.

While it’s possible to crack the encryption in less time, each misstep would push back the subsequent cool-down period before the software would allow for another go.

A few weeks before the Nov. 13 attacks on Paris, the DOJ employed a new strategy to coerce Apple into handing over the keys to iOS – and it’s a good one. The tech world is still awaiting Apple’s counterpunch.

Roughly a year ago, then U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder frame the debate on encryption and stated the DOJ’s stance while speaking at the Global Alliance Against Child Sexual Abuse Online.

“Recent technological advances have the potential to greatly embolden online criminals, providing new methods for abusers to avoid detection,” Holder said, adding that there are those who take advantage of encryption in order to hide their identities and “conceal contraband materials and disguise their locations.”

The Information Technology Industry Council, which speaks on behalf of the high-tech industry, sees all of the above issues as reasons everyone needs encryption.

“Encryption is a security tool we rely on everyday to stop criminals from draining our bank accounts, to shield our cars and airplanes from being taken over by malicious hacks, and to otherwise preserve our security and safety,” said Dean Garfield, president and CEO of ITI.

While stating the ITI’s deep “appreciation” for the work done by law enforcement and the national security community, Garfield said there is no sense in weakening the security just to improve it.

“[W]eakening encryption or creating backdoors to encrypted devices and data for use by the good guys would actually create vulnerabilities to be exploited by the bad guys, which would almost certainly cause serious physical and financial harm across our society and our economy,” he explained.

Paris as a Talking Point

In the wake of the recent Paris Attack, U.S. officials have again reissued their call for software developers – Apple, Google and others – to provide law enforcement agencies with keys to the backdoor of operating systems with government-grade encryption.

While there is still no evidence that law enforcement agencies, with encryption keys in hand, could have given police on the ground in Paris a game-changing heads up of the attacks. Nevertheless, Paris has been turned into a talking point said Michael Morell, a former deputy director of the CIA, who stated that the tragic events will reshape the encryption debate.

“We have, in a sense, had a public debate [on encryption],” said Morell. “That debate was defined by Edward Snowden.” Although, instead of what the former NSA contractor and leaker had done, the issue of encryption will now be “defined by what happened in Paris.”